Introduction By Adriana Valderrama

Aodán McCardle

Emerging Forms

(8th of October – 7th of November 2022)

At some point in our childhood we have drawn and we have done so before we started to read and write. Drawing in childhood is unconscious; it is more about communicating, letting perceptions come out through visual signs. Drawing deliberately, on the other hand, is a tentative and conscious investigation of the forms we see and the structures that compose them. We try to see if our hand responds to our eye in our attempts to capture reality, but we also try to see if the hand discovers its own ability to move and with it the adjustment of the inside and the outside.

For some of us, drawing reminds us of the time when we were free to play and investigate with pleasure the sensitive structure of the world we were beginning to discover. It was a time when we could not understand or express in words what we felt. That is why drawing helped to give us an outlet for what could not be said in words, and also helped us to enjoy a sensitive rehearsal as if we were playing.

In this way, drawing not only conveys the nostalgia of our own childhood, of our own hesitant discovery of the world, but also serves to remember the childhood of our species, for drawing is the basis of art, and here we must undoubtedly situate the beginning of its history and of our history as beings who learned to hunt, to produce fire and to draw.

For example, John Berger takes us back to the dawn of art when he describes his encounter with cave-drawings in the text Le Pont d’Arc (2005) in this poetic way

Silence. I turn off the helmet lamp. A darkness. In the darkness the silence becomes encyclopedic, condensing everything that has occurred in the interval between then and now.

On a rock in front of me, a cluster of red squarish dots. The freshness of the red is startling. As present and immediate as a smell, or as the colour of flowers on a June evening when the sun is going down. These dots were made by applying red oxide pigment to the palm of a hand and then pressing it against the rock. One particular hand has been identified on account of a disjointed little finger, and another imprint of the same hand has been found elsewhere in the cave. (…)

I crawl into a low cup-shaped annex - four metres in diameter - and there, drawn in red on its irregular curving sides, are three bears - male, female and cub, as in the fairy story to be told many millennia later. I squat there, watching. Three bears and behind them two small ibex. The artist conversed with the rock by the flickering light of his charcoal torch.

A protruding bulge allowed the bear's forepaw to swing outwards with its awesome weight as it lolloped forward. A fissure followed precisely the line of an ibex's back. The artist knew these animals absolutely and intimately; his hands could visualise them in the dark.

What the rock told him was that the animals - like everything else which existed - were inside the rock, and that he, with his red pigment on his finger, could persuade them to come to the rock's surface, to its membrane surface, to brush against it and stain it with their smells.

These drawings that Berger describes are amongst the earliest man-made drawings ever found, they are in the Chauvet cave in France. The fascinating thing about these drawings is that they were made before our language took its present form.

John Berger’s interest in these drawings is not a simple coincidence, this poetic and fine description of his visit to the Chauvet cave is the result of one who writes from the experience of having been both an artist using drawing and a writer.

Not many people decide to dedicate themselves to two such diverse fields, but this intrinsic connection between drawing and writing has always been present in arts and humanities for it is clear that we have entered into writing through drawing, and that is the reflection that Berger develops in his text, the possibility of conceiving an art (drawing) under the form of this other art (writing).

Both when we draw and when we write we try to see if our hand responds to our thought or to our eye in our attempts to capture and represent reality, in that sense, we are not very different from our ancestor who painted the three bears in the Chauvet cave. As Roland Barthes, another writer who made drawings, says in his text Writing (1976):

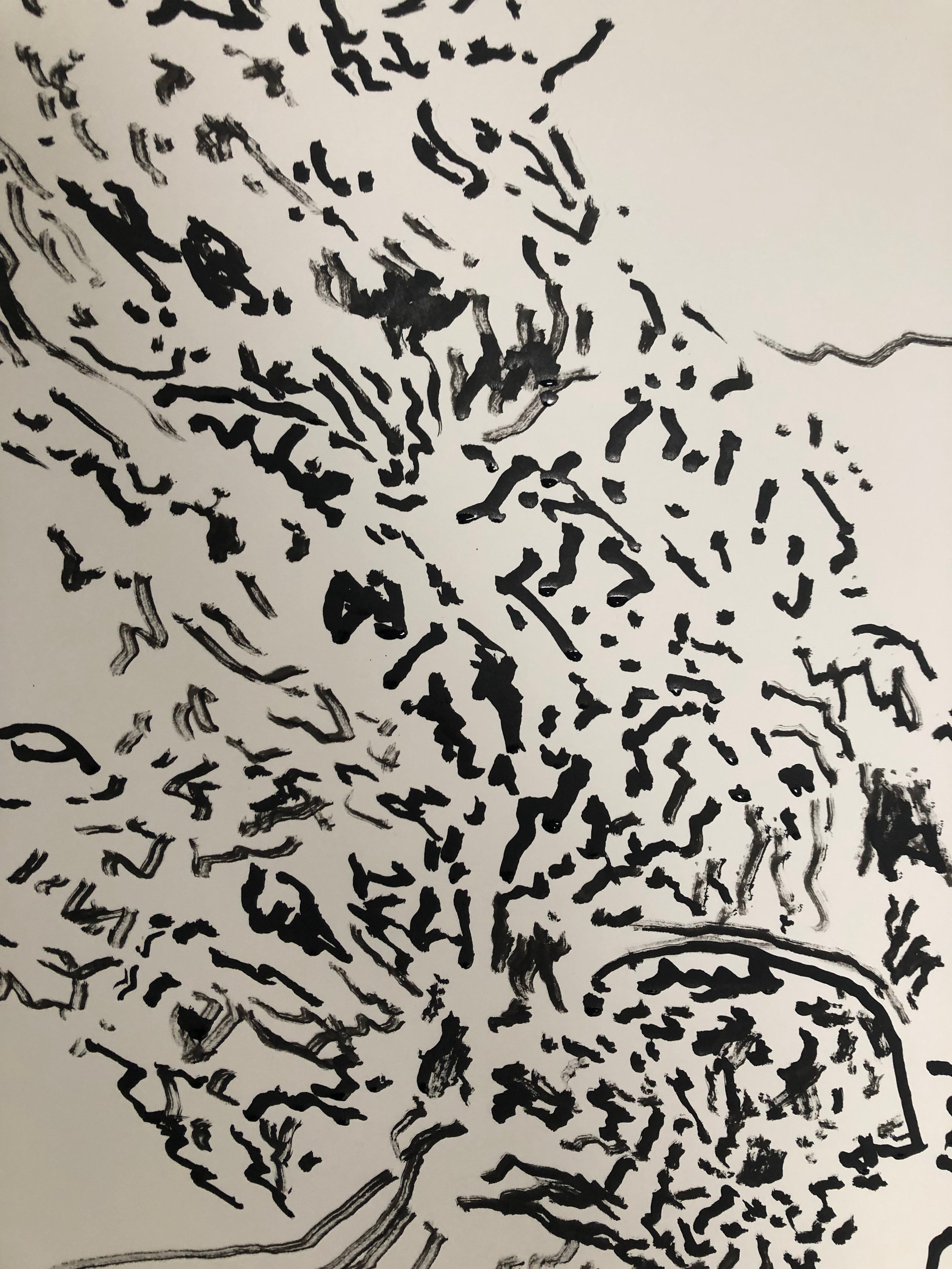

I have often wondered why I like to write (by hand, that is), to the point that, on many occasions, the pleasure of having in front of me (like a carpenter’s bench) a beautiful sheet of paper and a good pen it compensates, in my eyes, for the often thankless effort of intellectual work: while I reflect on what I have to write (that is what is happening now), I feel how my hand acts, turns, binds, dives, rises and, many times, Sometimes, through the game of corrections, he crosses out or explodes the line, and widens the space to the margin, thus constructing, from minute and apparently functional strokes (the letters), a space that is simply that of art: I am artist, not because I figure an object, but, more fundamentally, because, in writing, my body enjoys tracing, rhythmically cleaving a virgin surface (the virgin being infinitely possible).

This pleasure of drawing and writing is ancient, as we can see in the cave drawings that Berger talks about and as Barthes develops later in his text when he tells us about a series of regularly spaced incisions that have been found on the walls of certain prehistoric caves. These incisions were not really writing “but their very rhythm denotes a conscious activity, probably magical or, more broadly, symbolic: the imprint, named, organized, sublimated (it doesn't matter) of a drive. The human desire to bleed (with the awl, the pen, the stylus, the quill) or to caress (with the brush, the felt)” (Barthes, 1976) has undoubtedly gone through many ups and downs that have hidden the bodily origin of writing; but it is enough that, from time to time, a painter incorporates graphic forms into their work, to lead us to this evidence: writing is not only a technical activity, but also a performative practice of enjoyment.

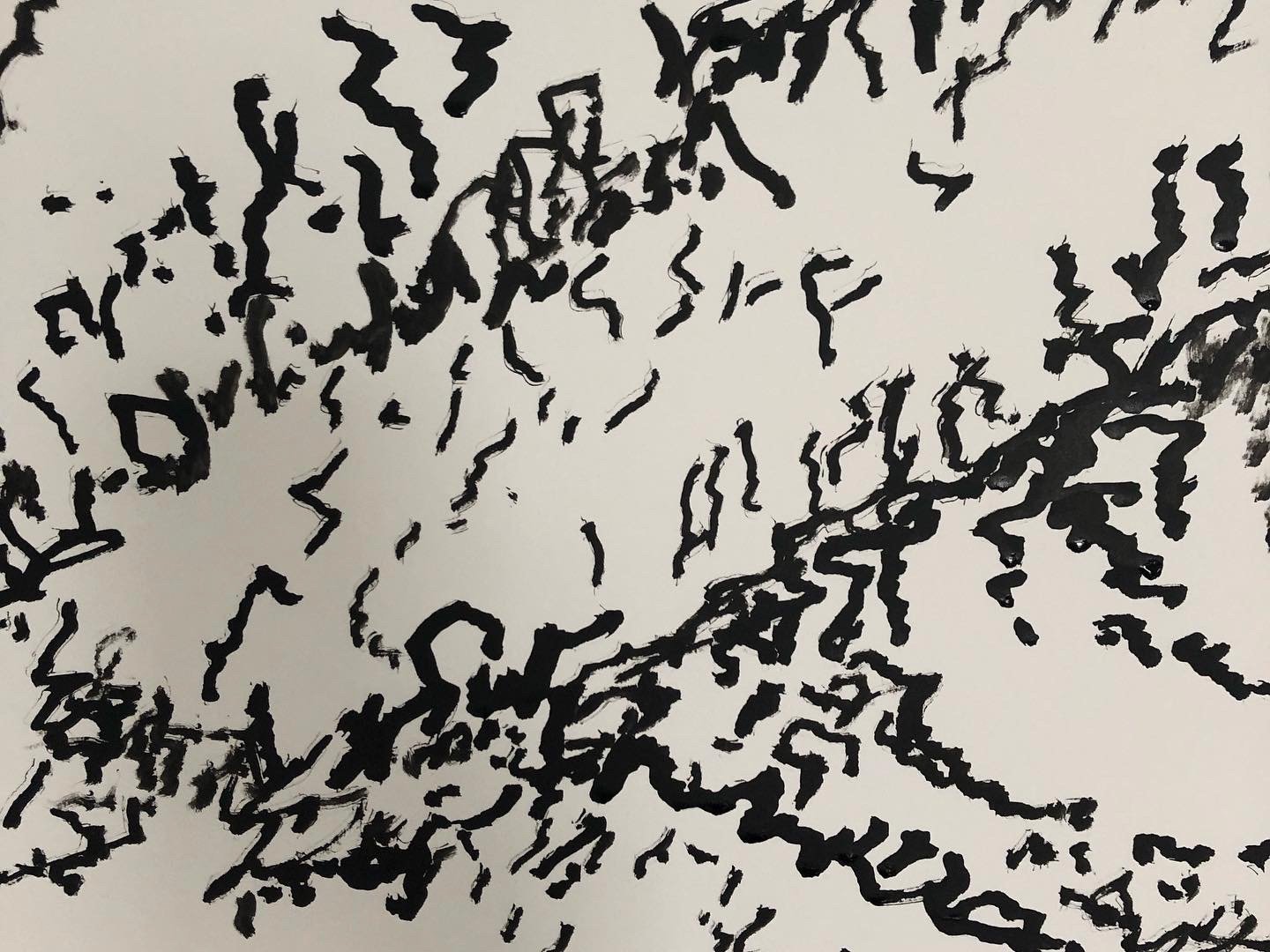

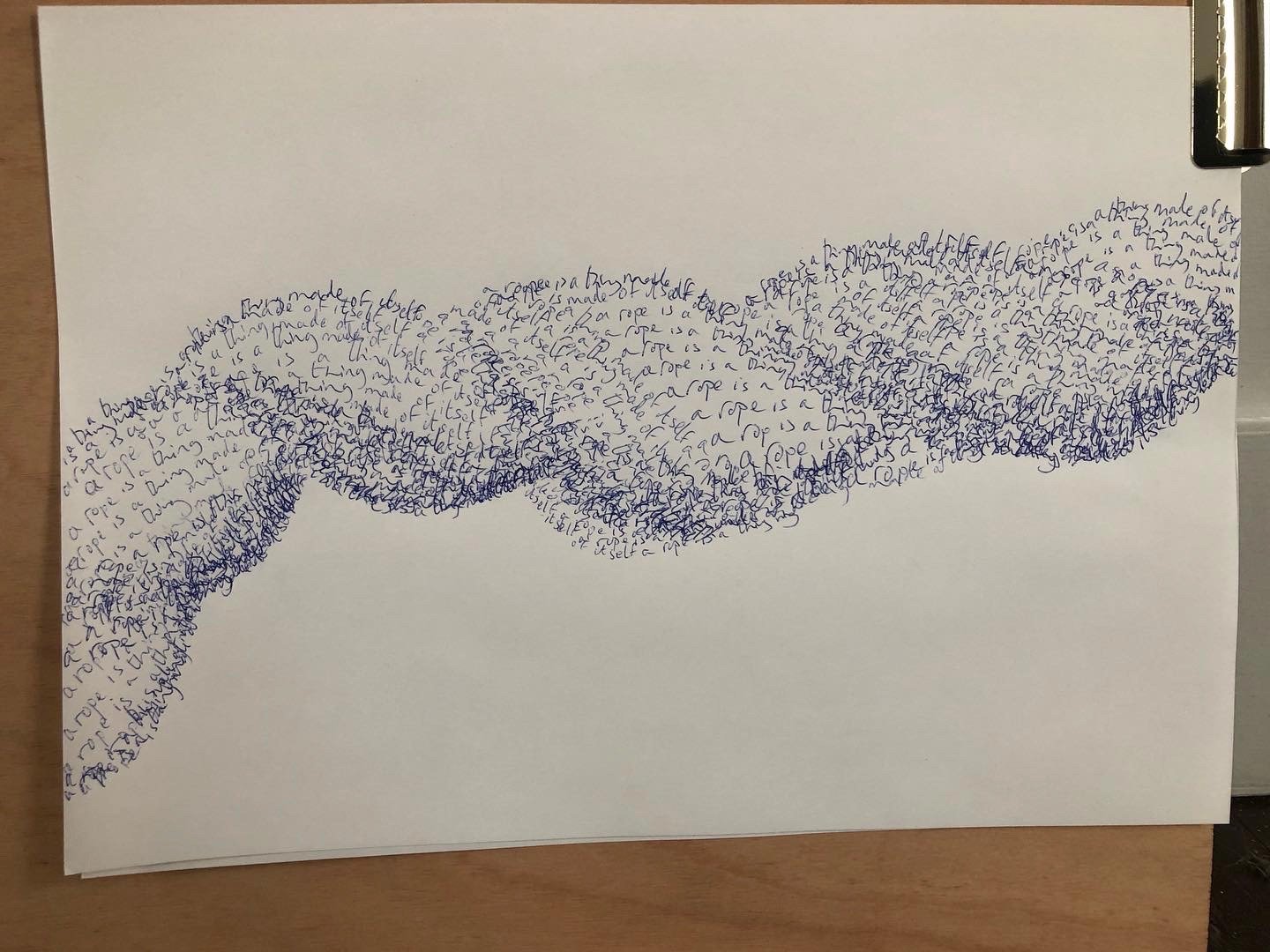

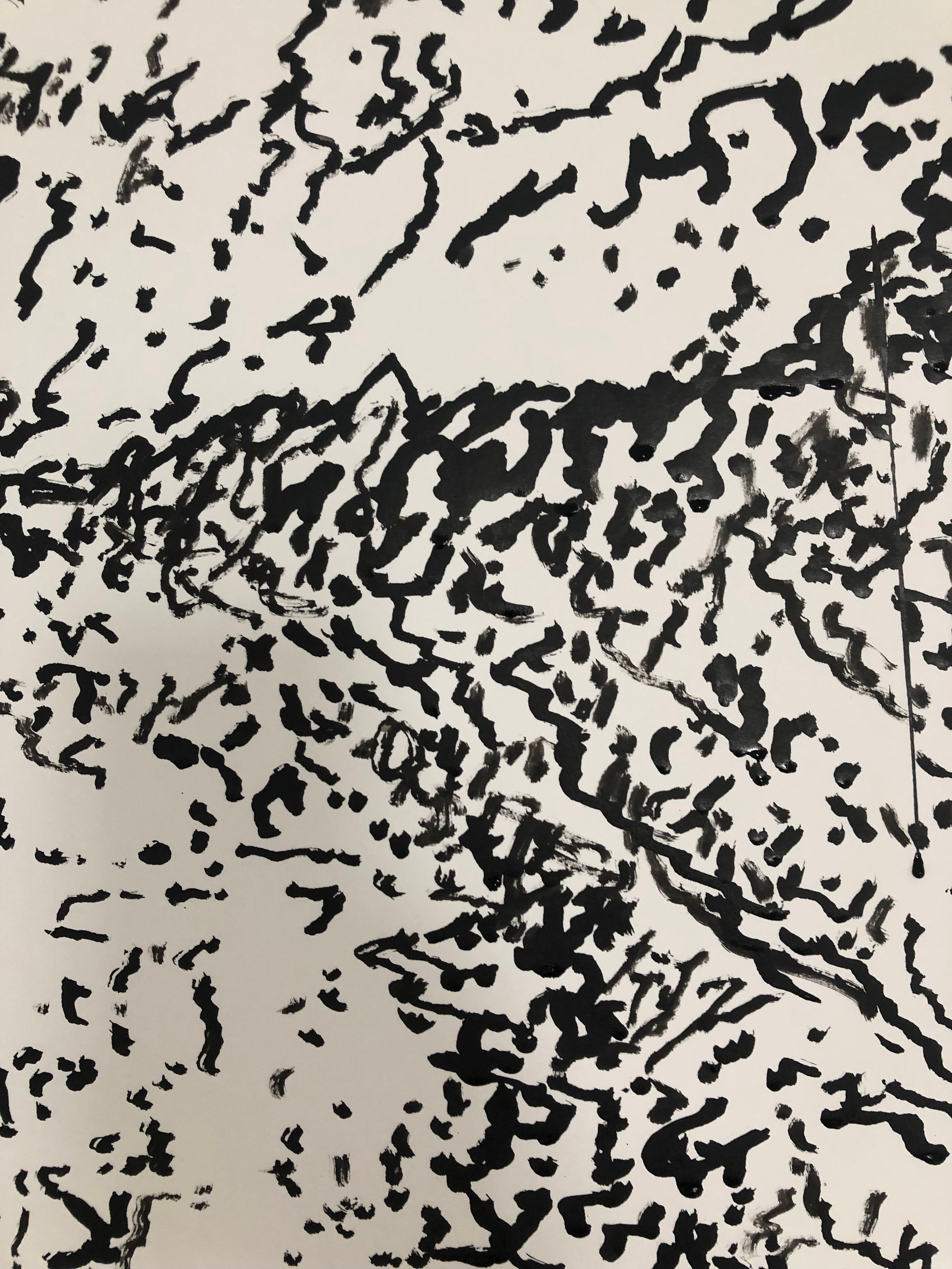

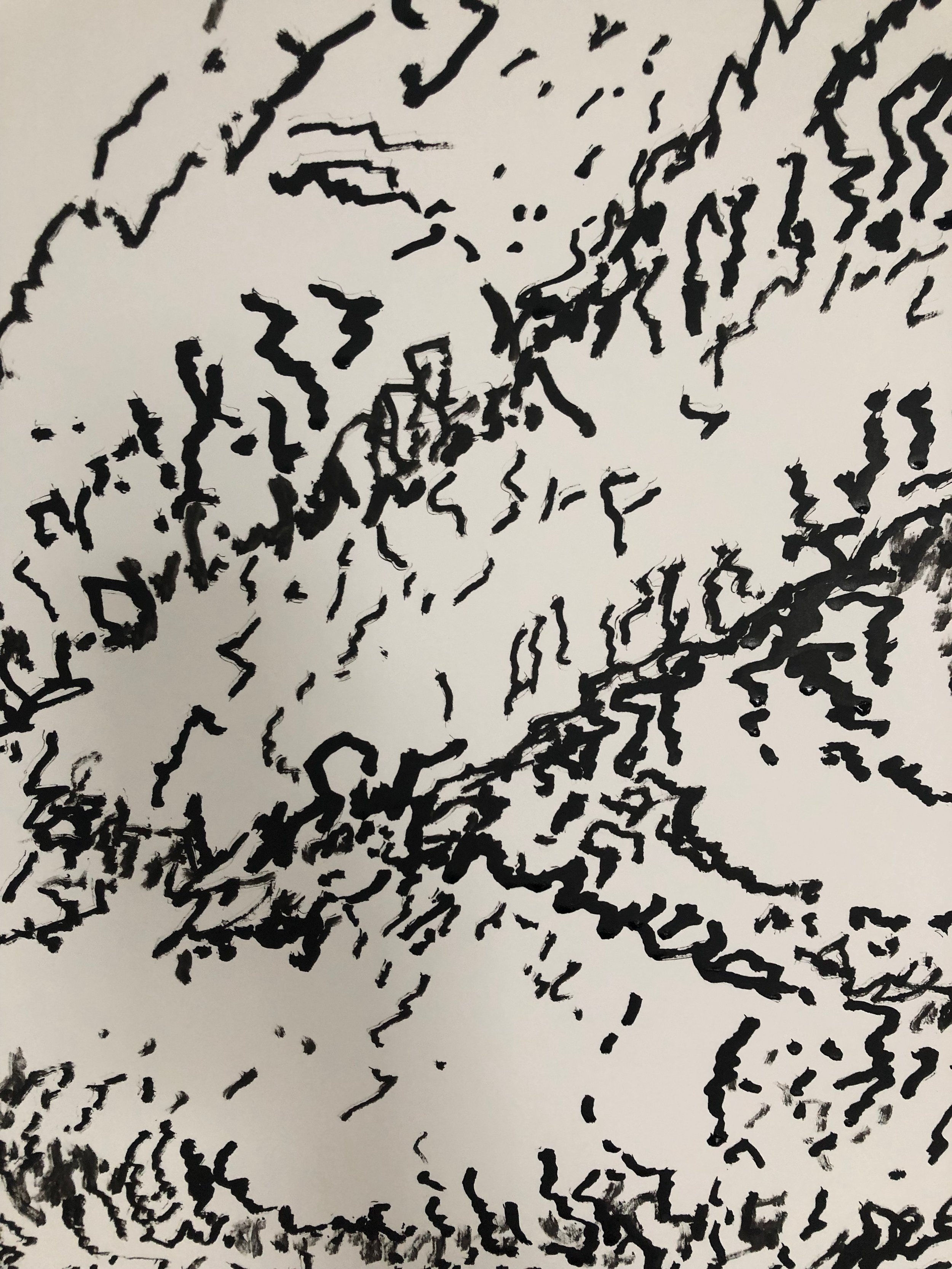

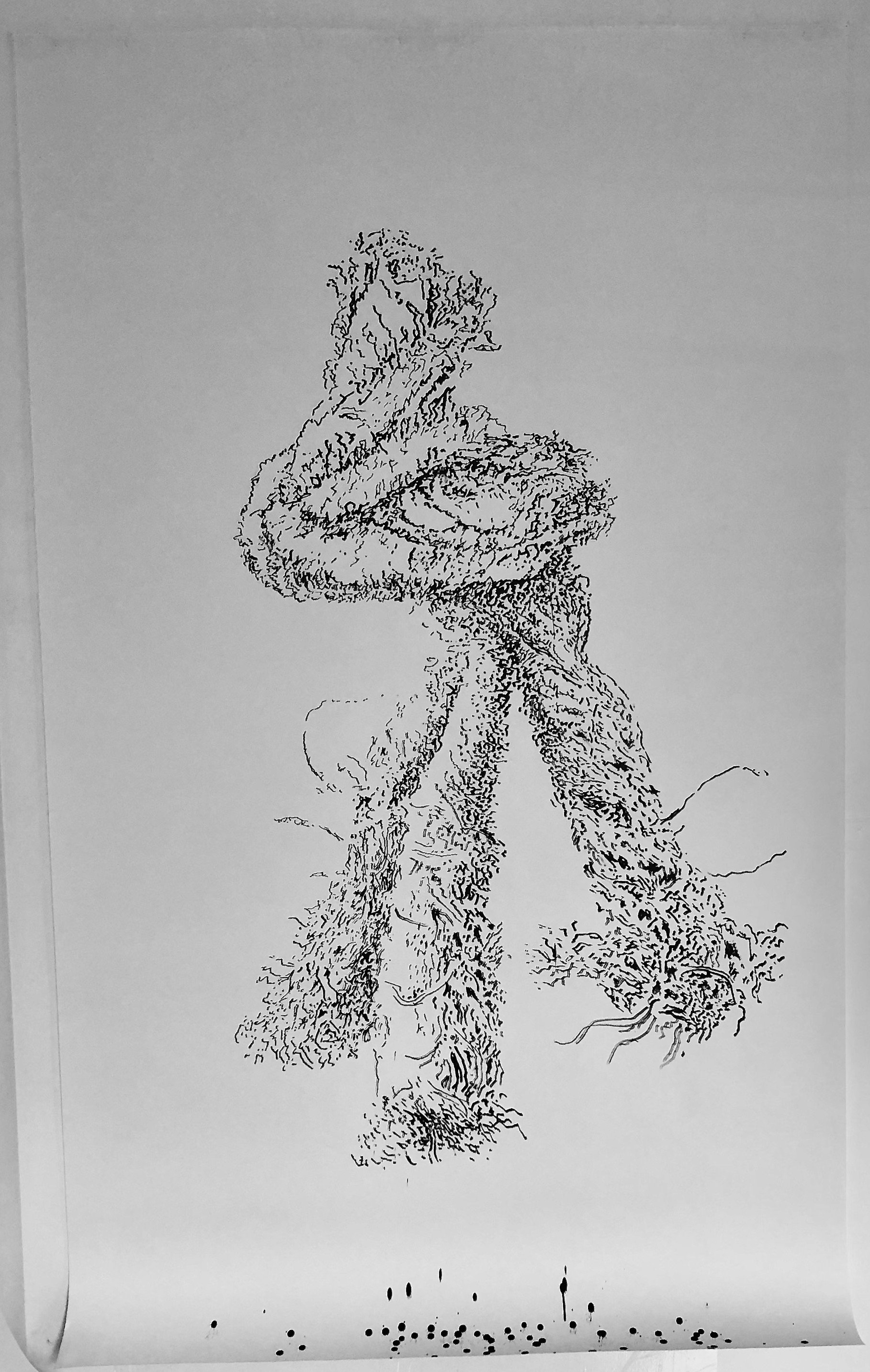

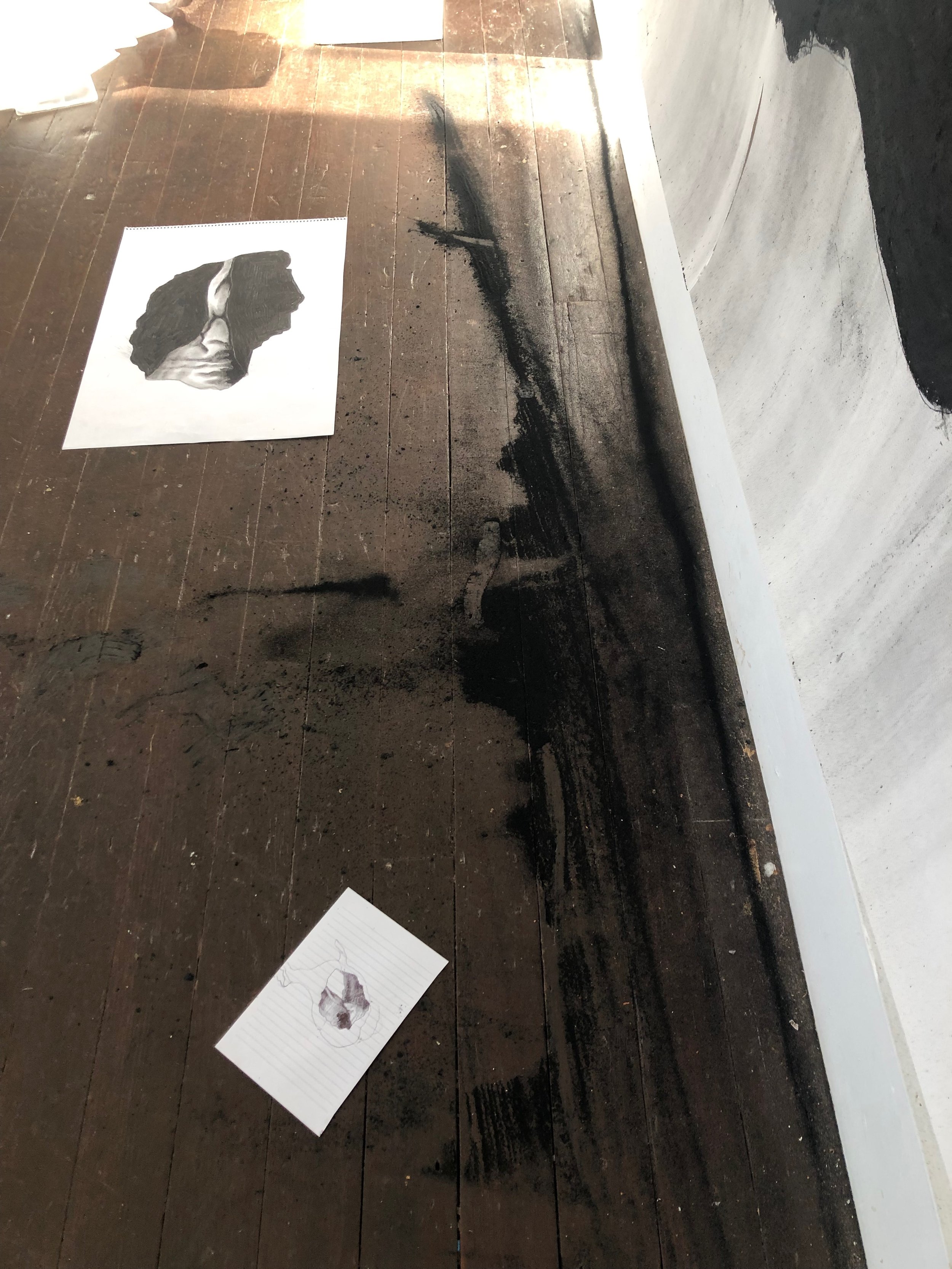

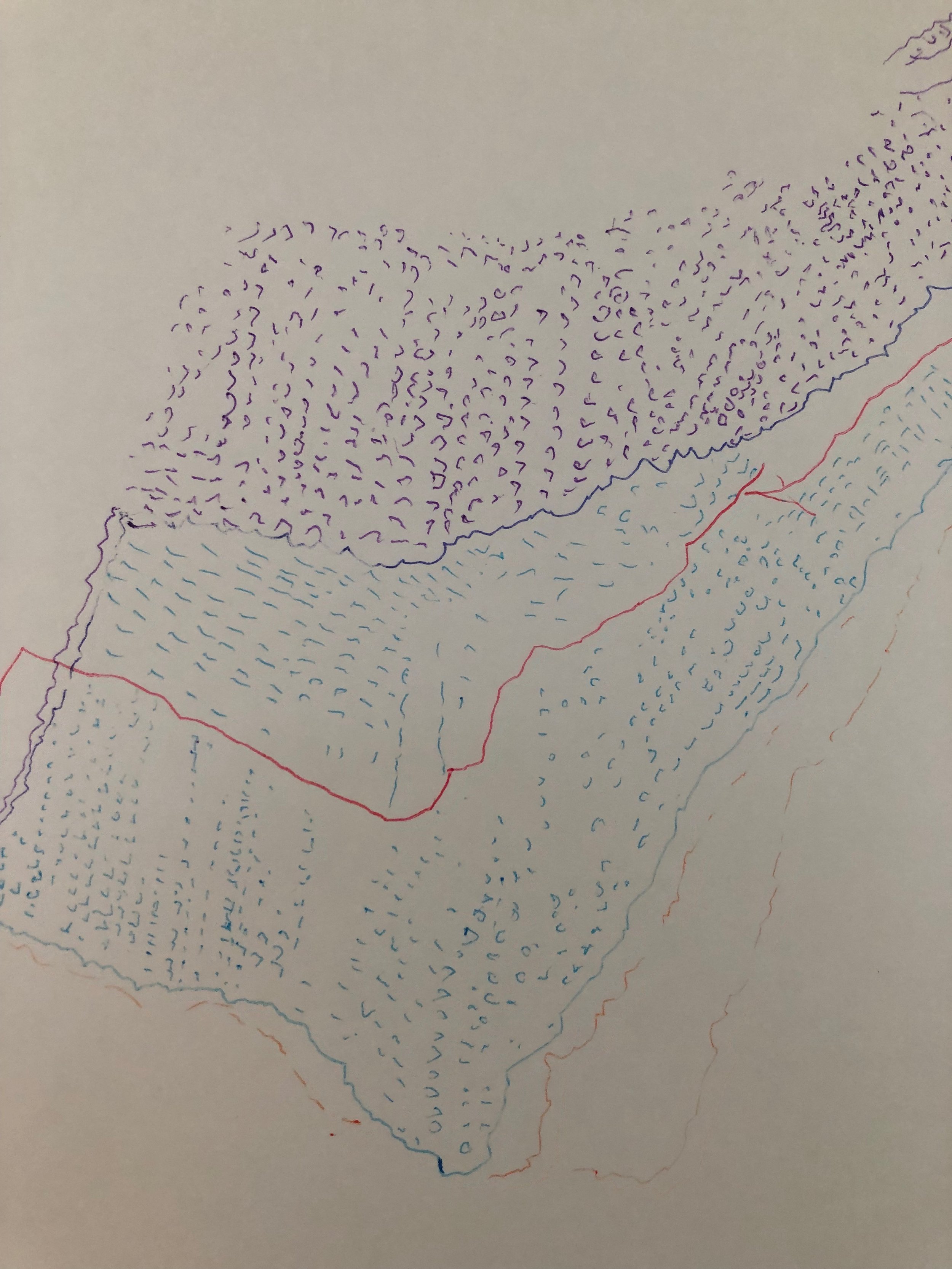

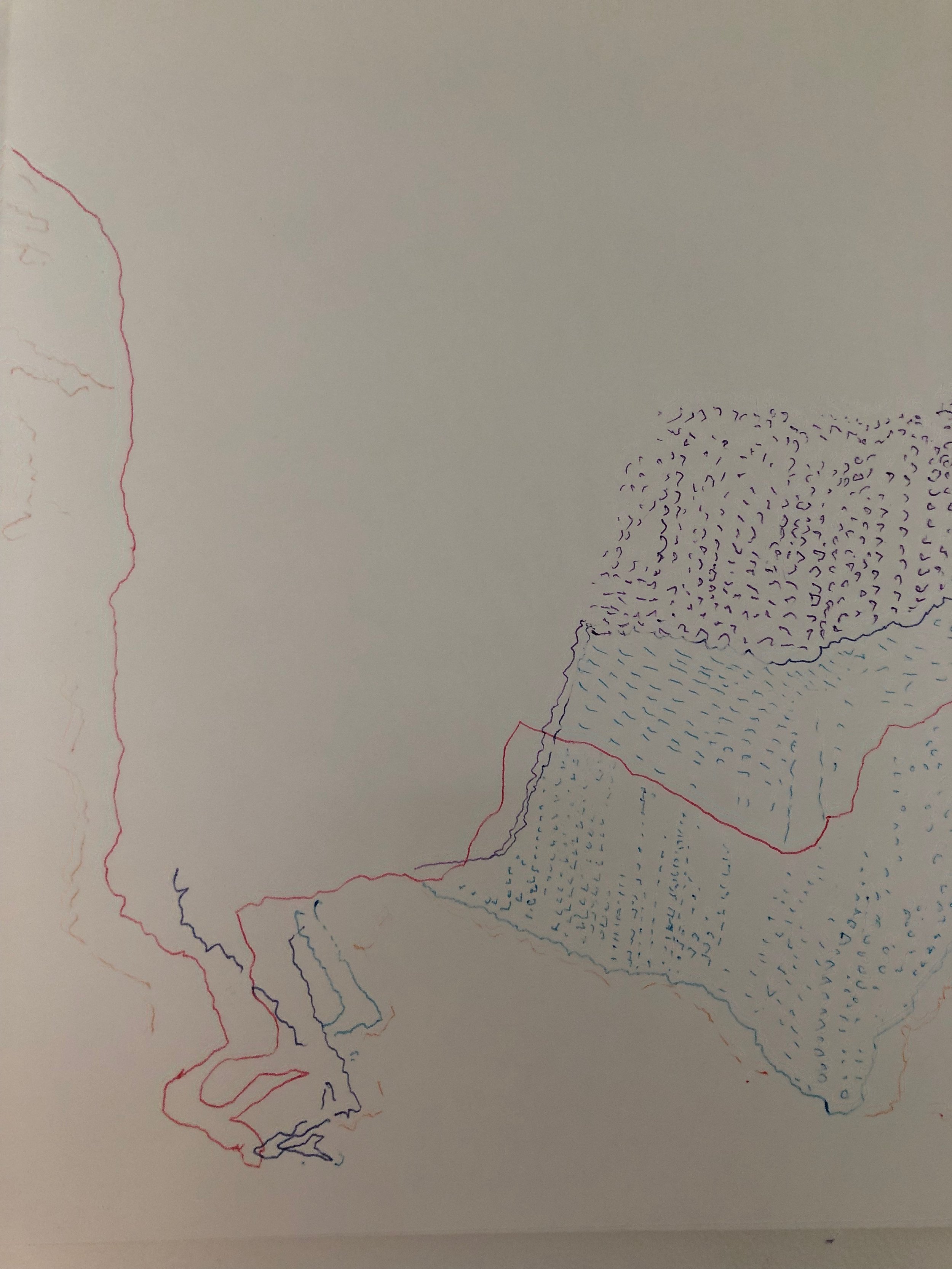

Emerging Forms, the new exhibition at Artlink presents the work of the artist Aodán McCardle, who since 2011 has concentrated specifically on combining writing and drawing in live performance, where the paintings and the drawings are a residue of these performances.

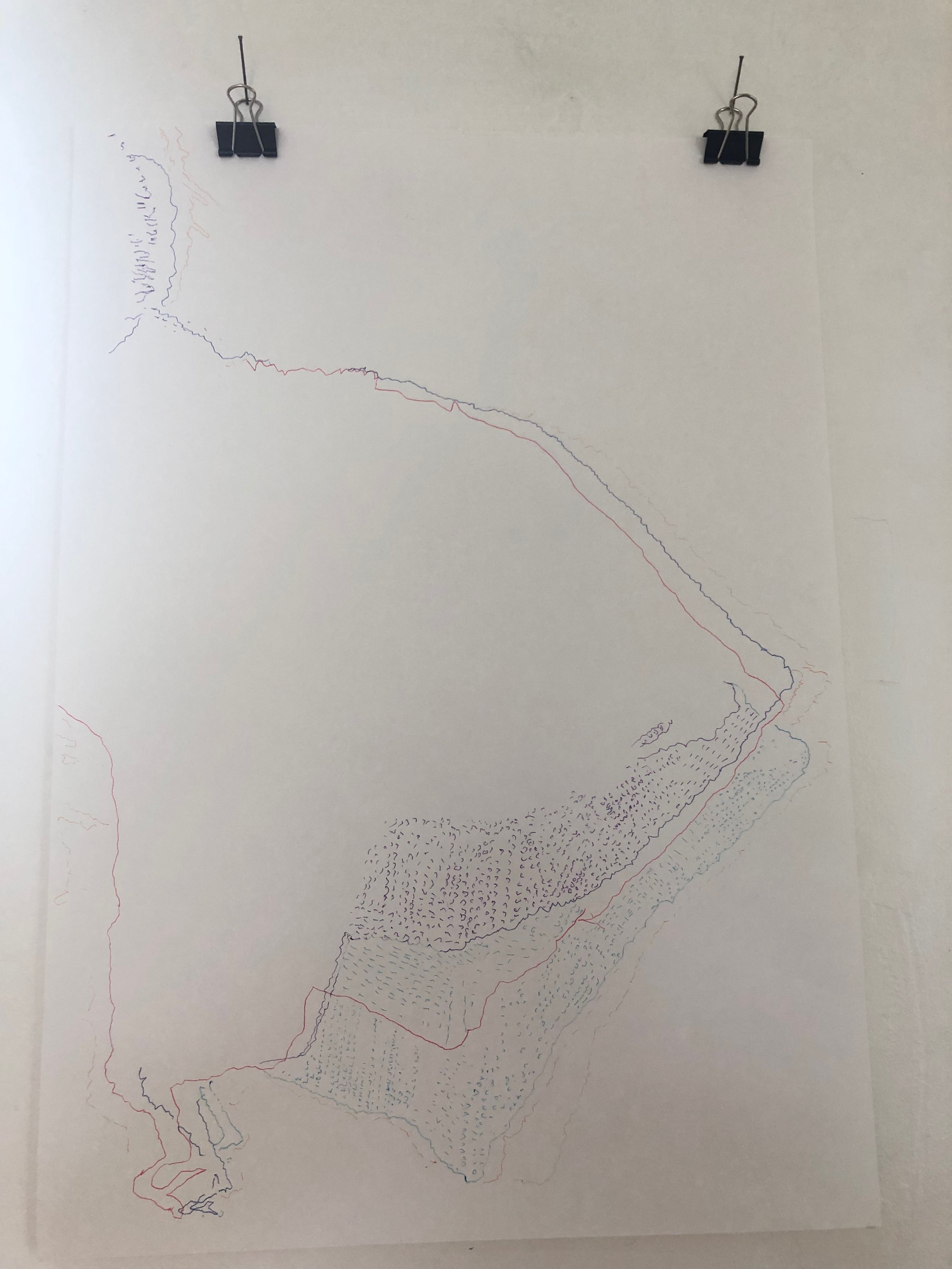

Aodán McCardle has opted for the improvisation and collaboration of performance as a methodology and technique between different states of writing, drawing and communication with others as a way of negotiating the changing language and social controls of the 21st century.

Performance, with its possibility of improvisation and collaboration, serves McCardle to foreground the contested status of the ego as the primary judge of value. Improvisation and collaboration as the lens and conductor of the back and forth between writing and drawing a subject, force him to relinquish control over it. In this way, Aodán McCardle seeks that his exploration of reality can be directed and designed by other potential influences of a subject’s atmosphere, to investigate those aspects of 21st century life that claim our social, public and personal spaces and seek to control our relationships, knowledge and gazes, whether through gender, cultural or economic inequalities. As he states, “my research into improvisational performance practice and collaborative writing and art turns that lens inwards during process and delivery”.

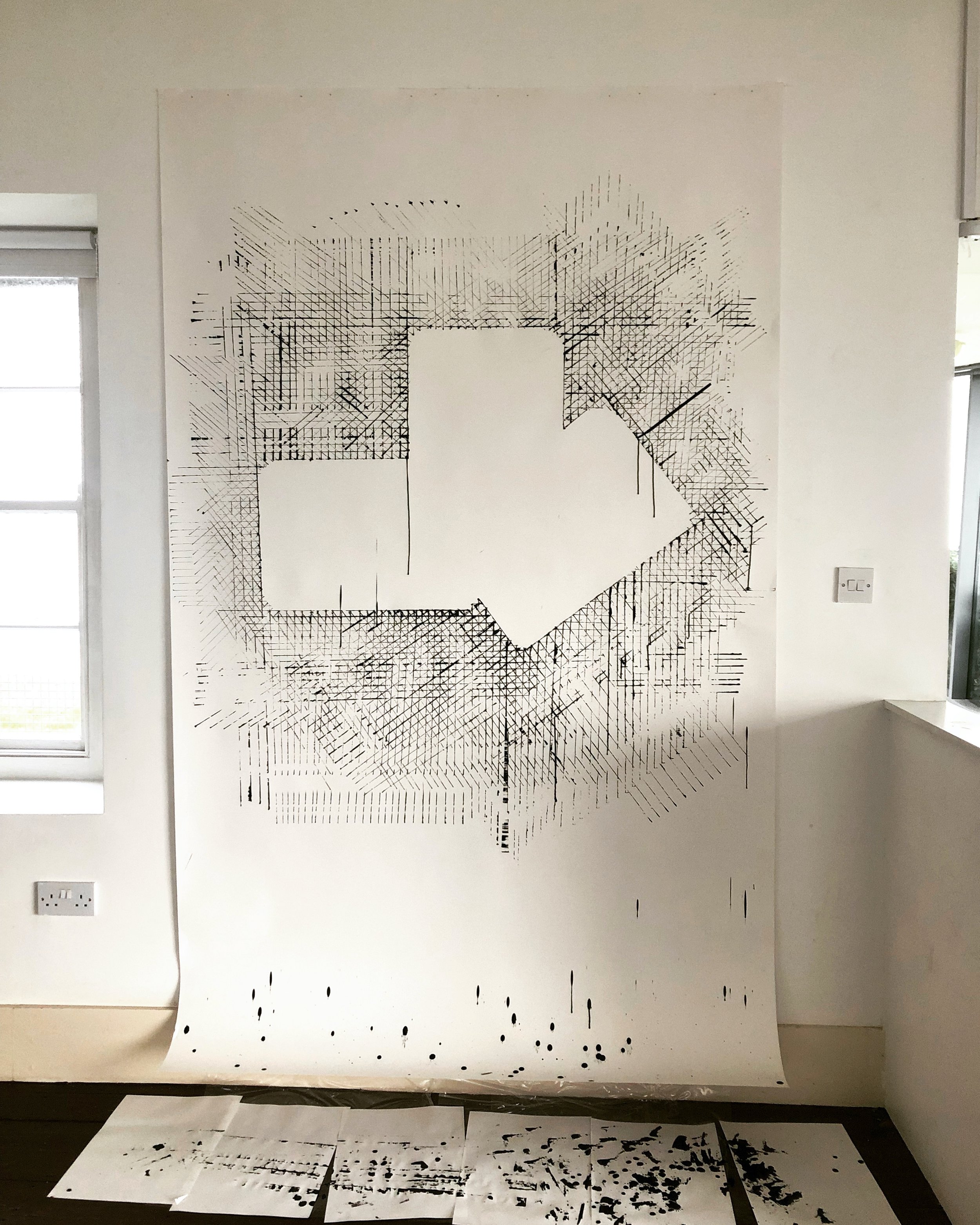

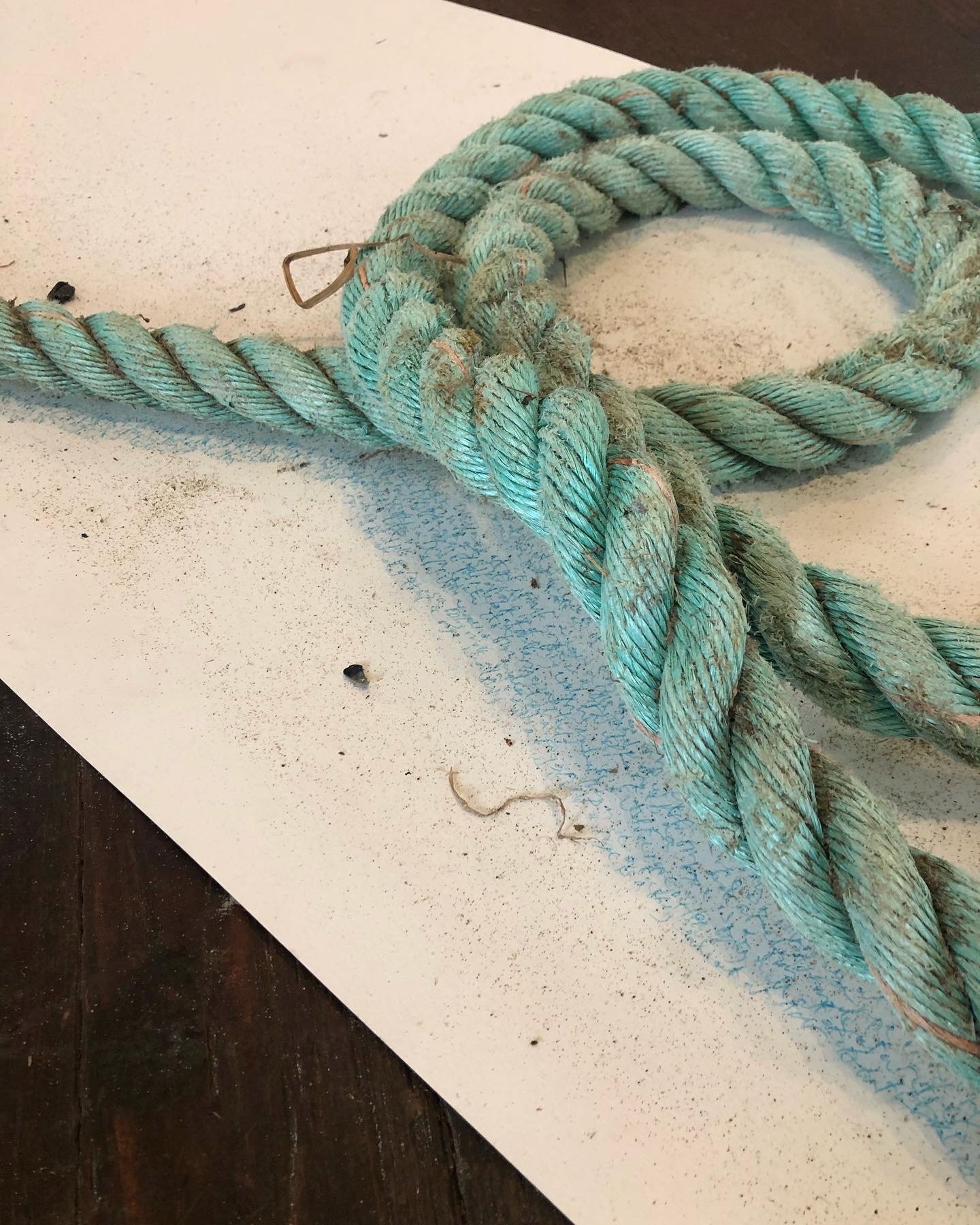

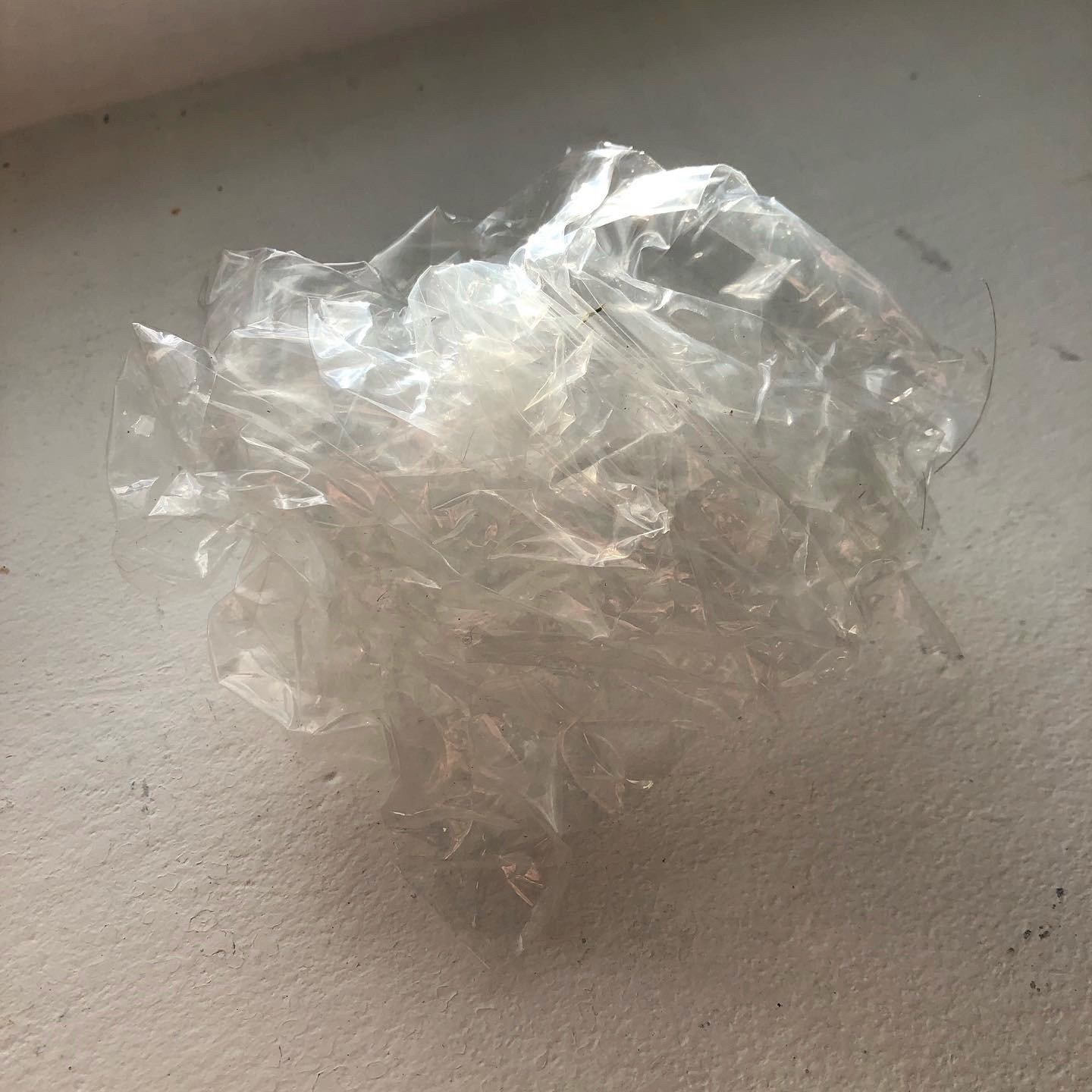

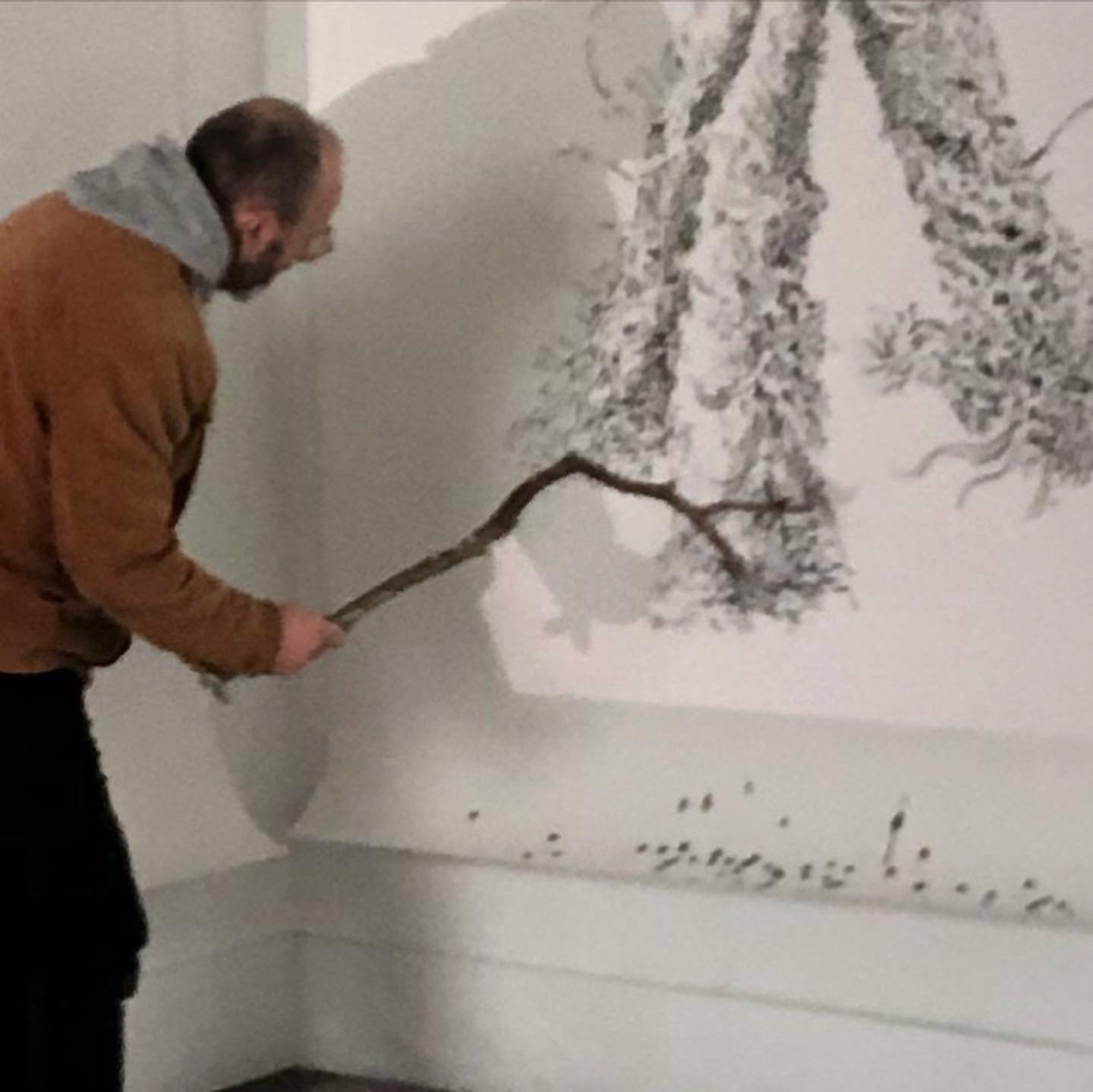

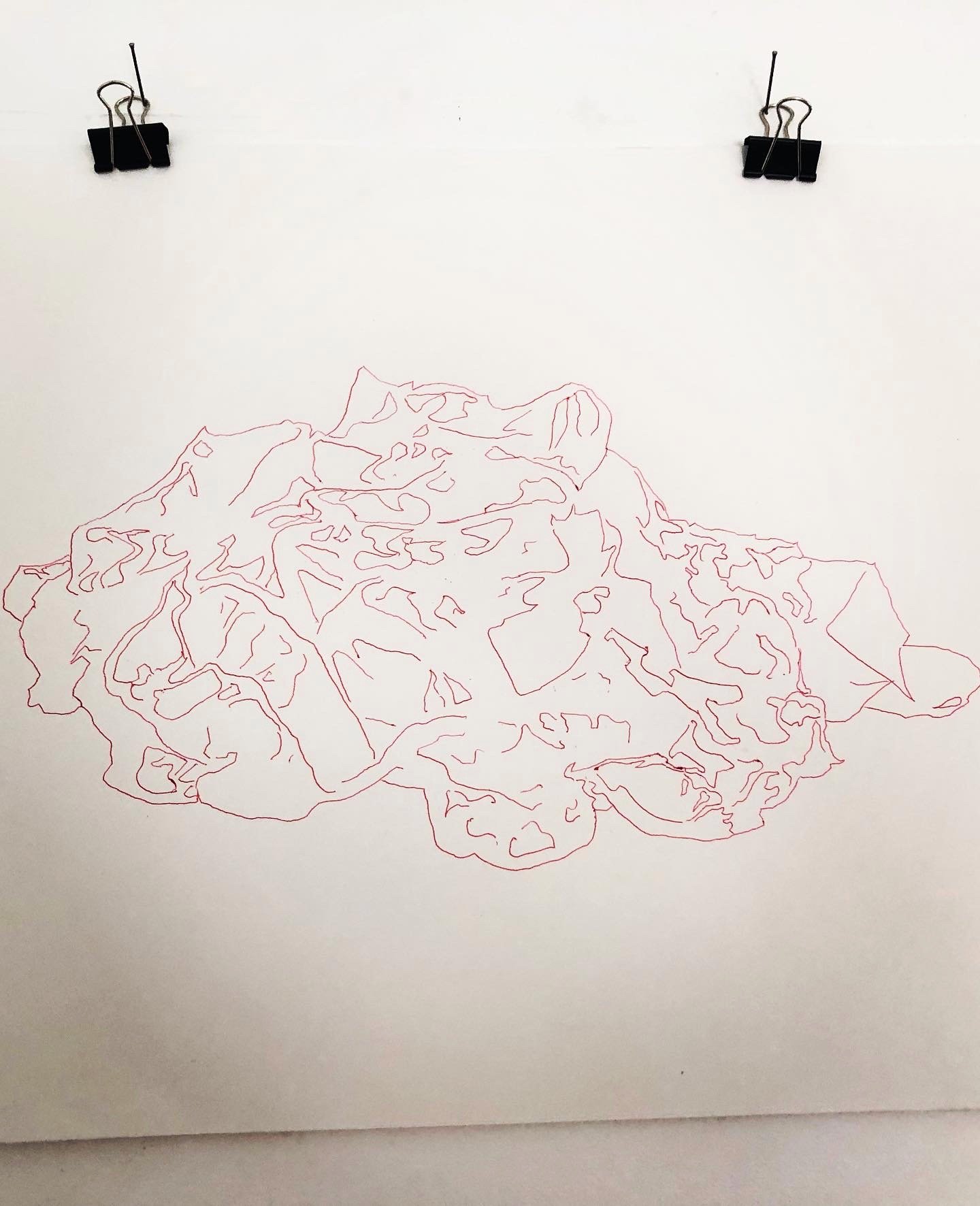

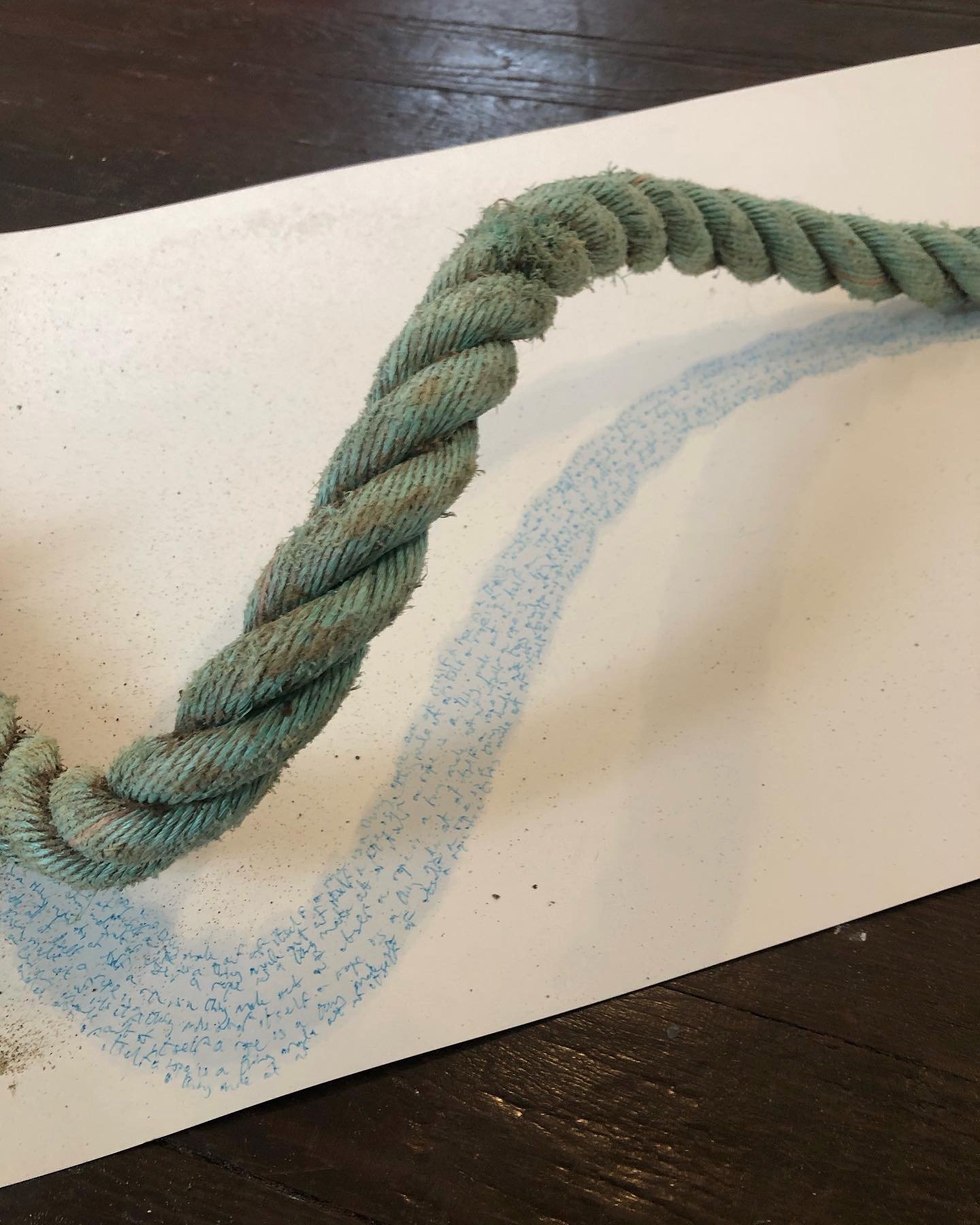

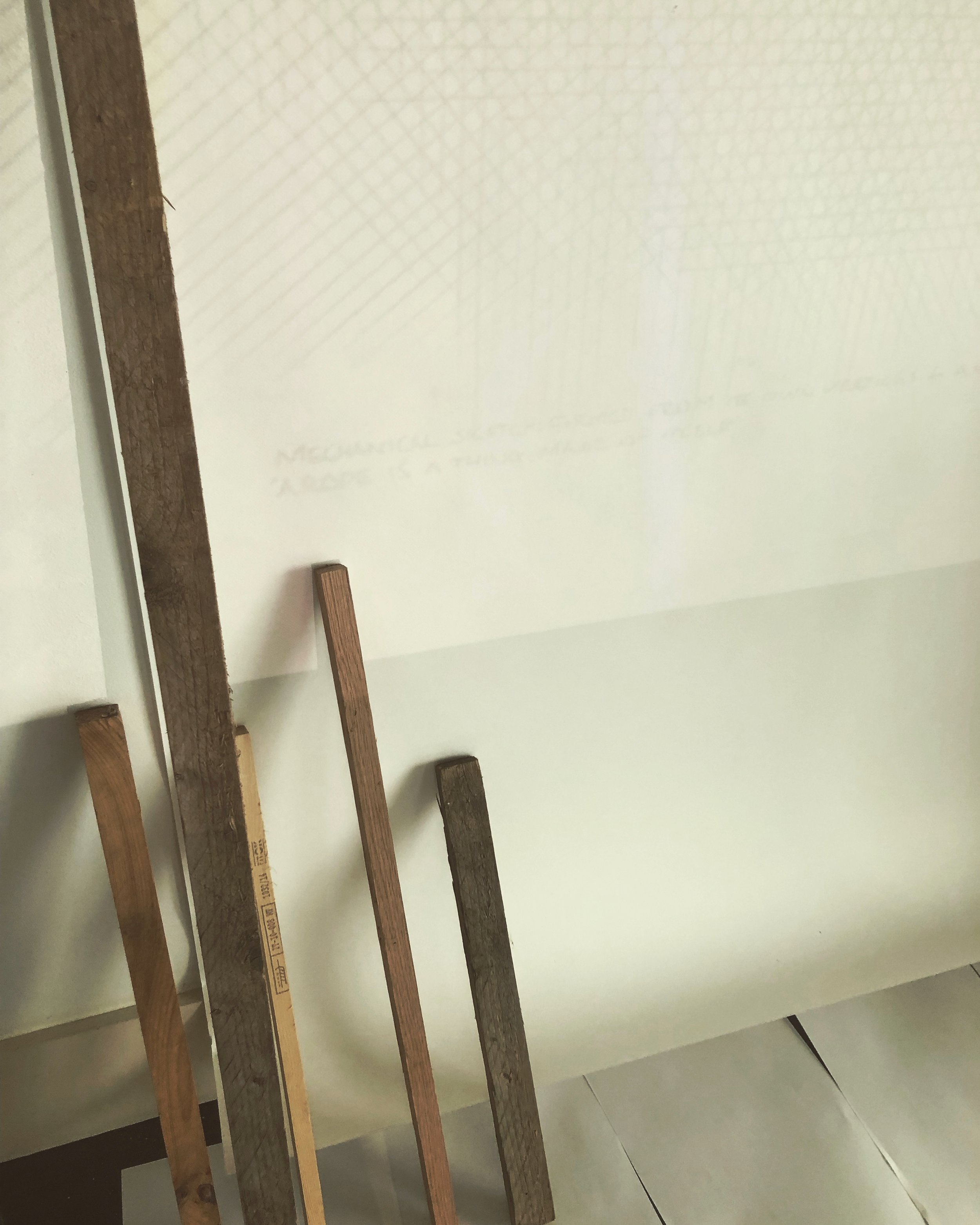

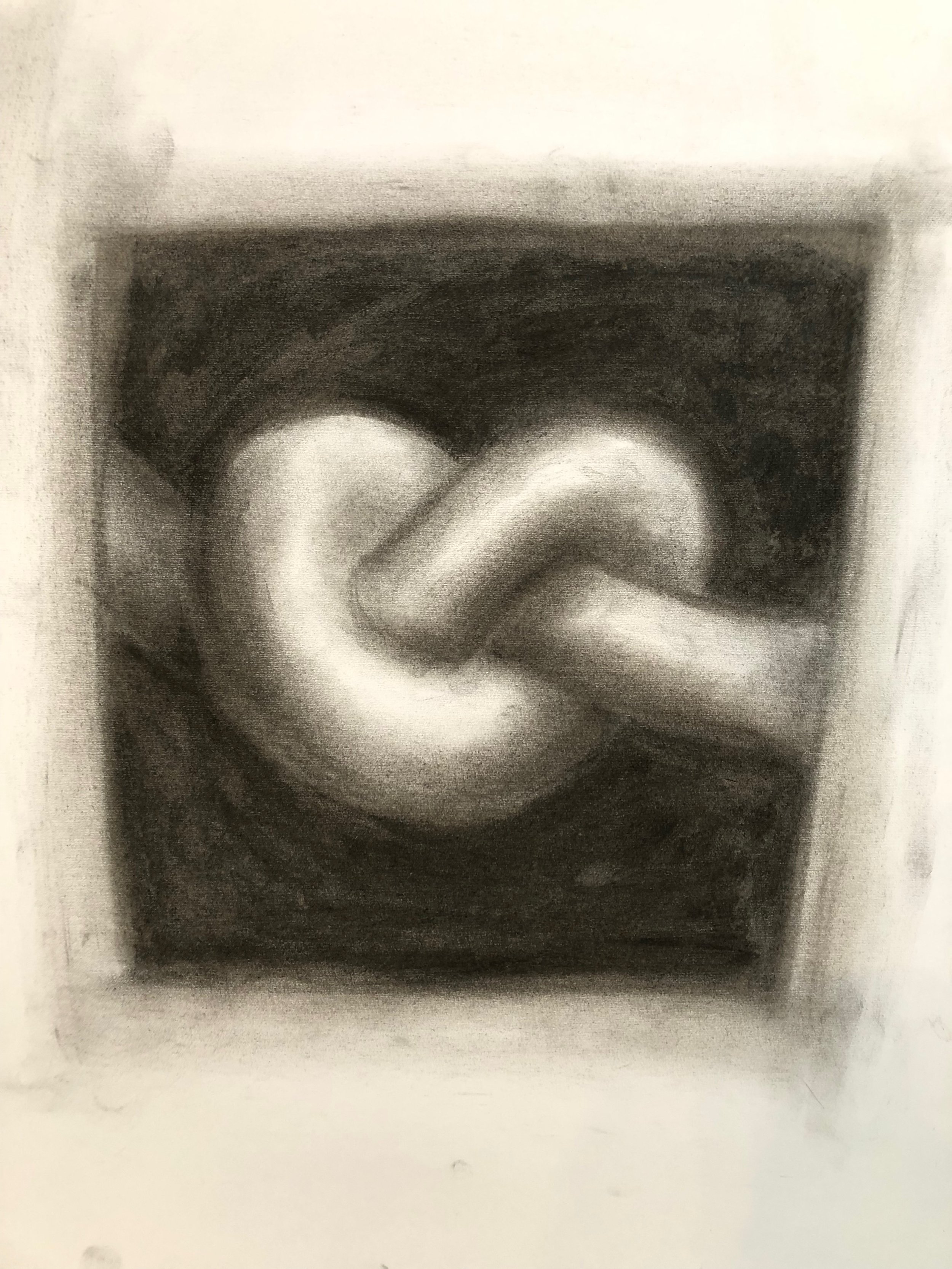

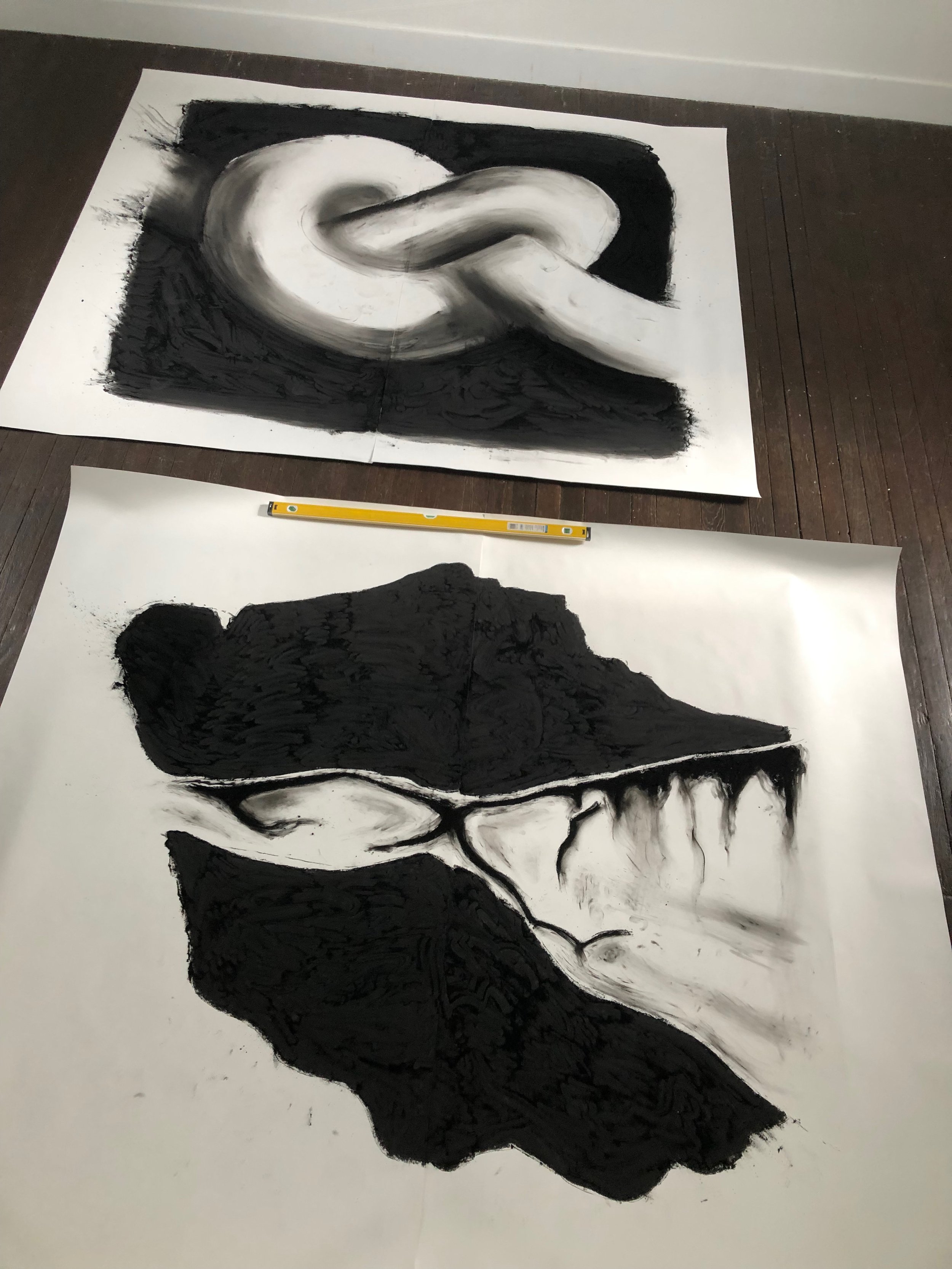

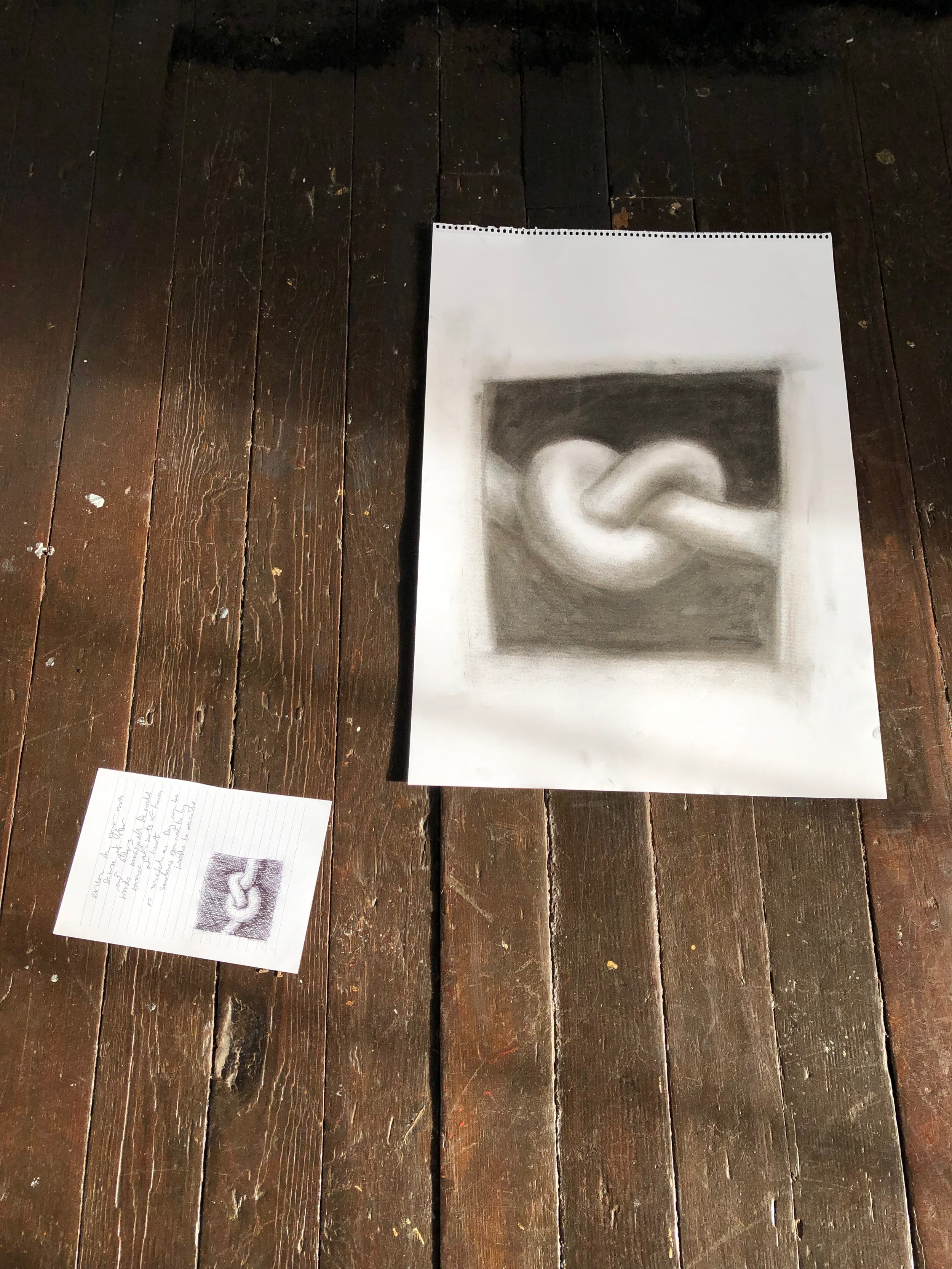

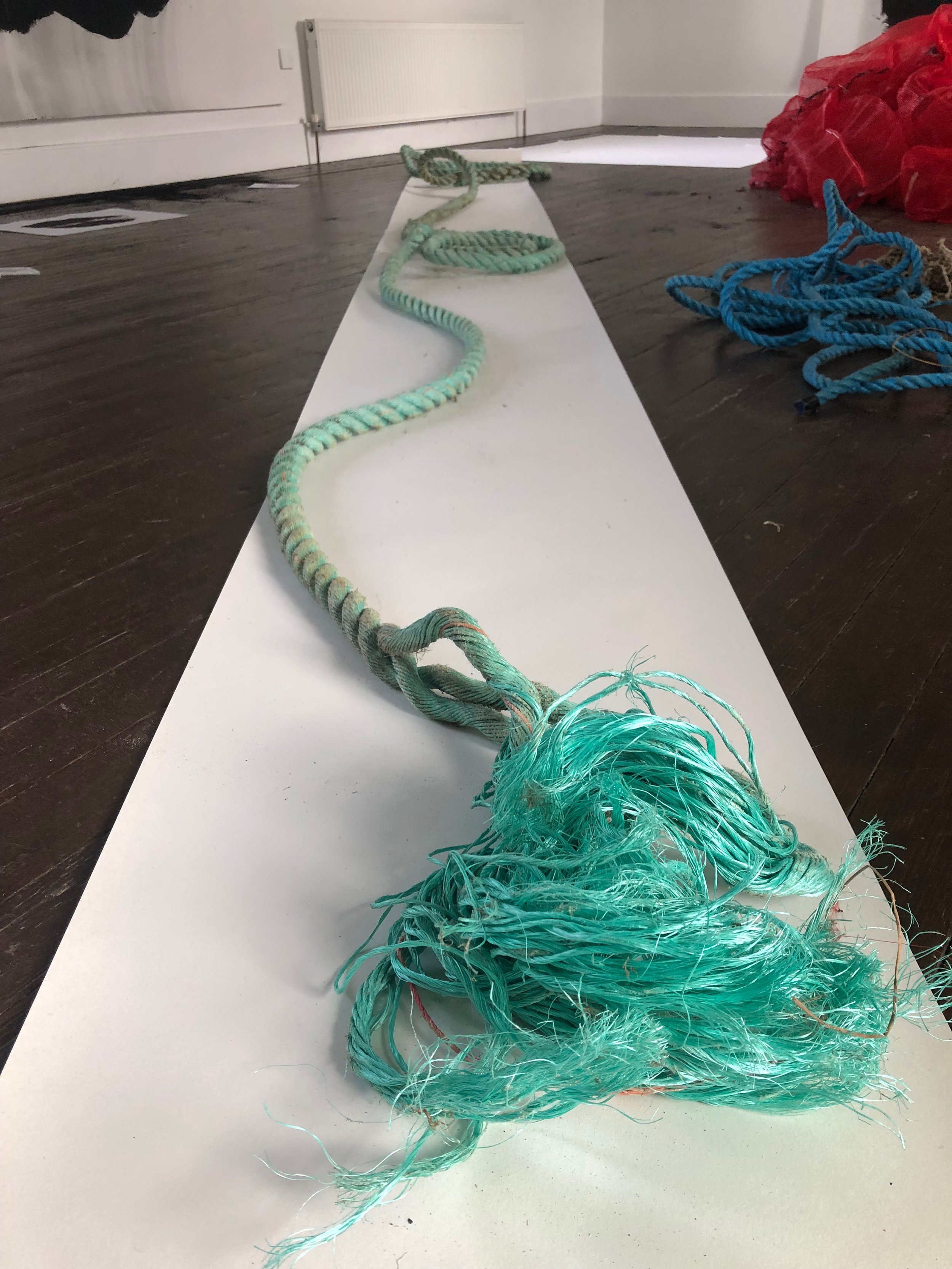

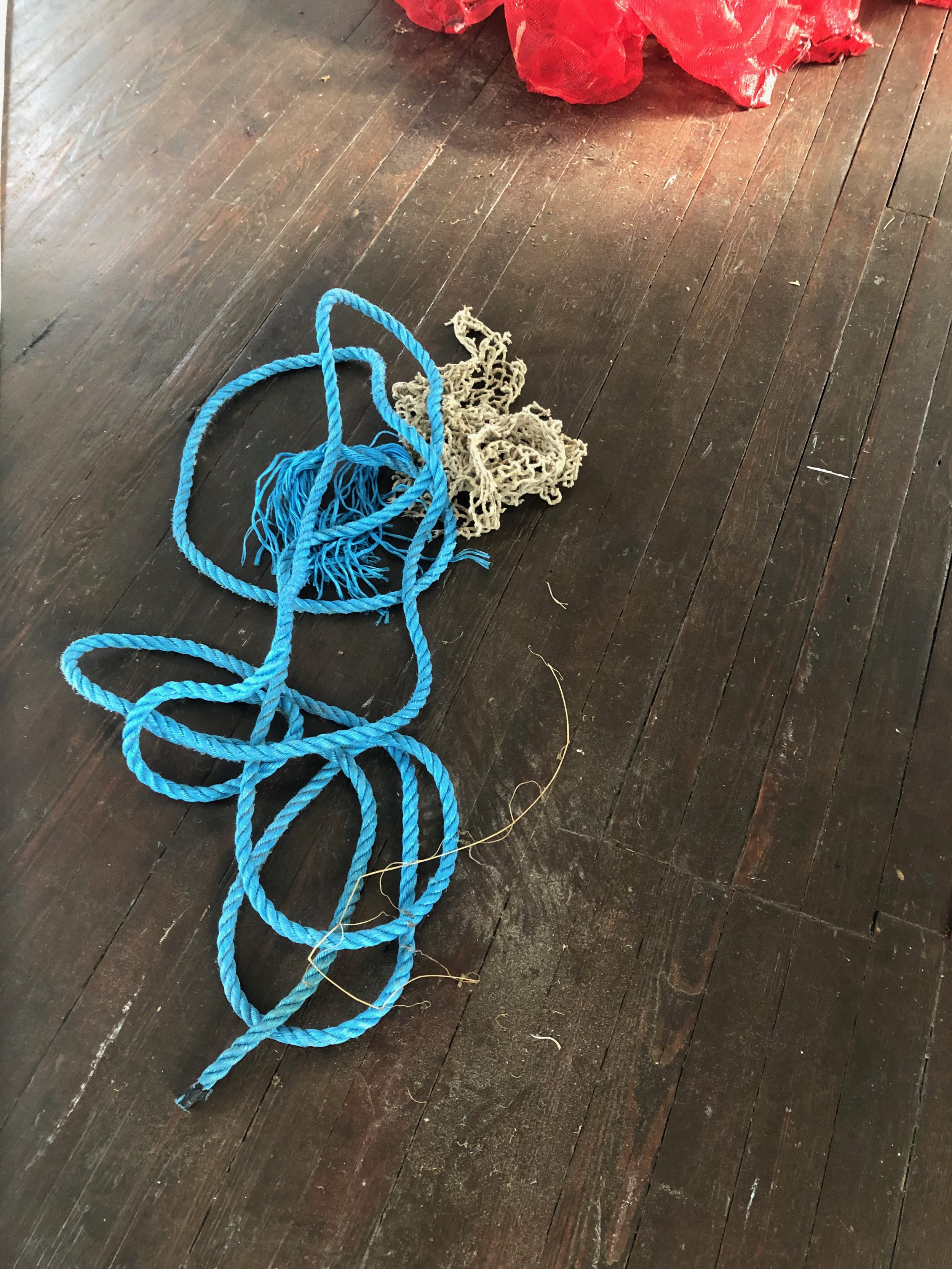

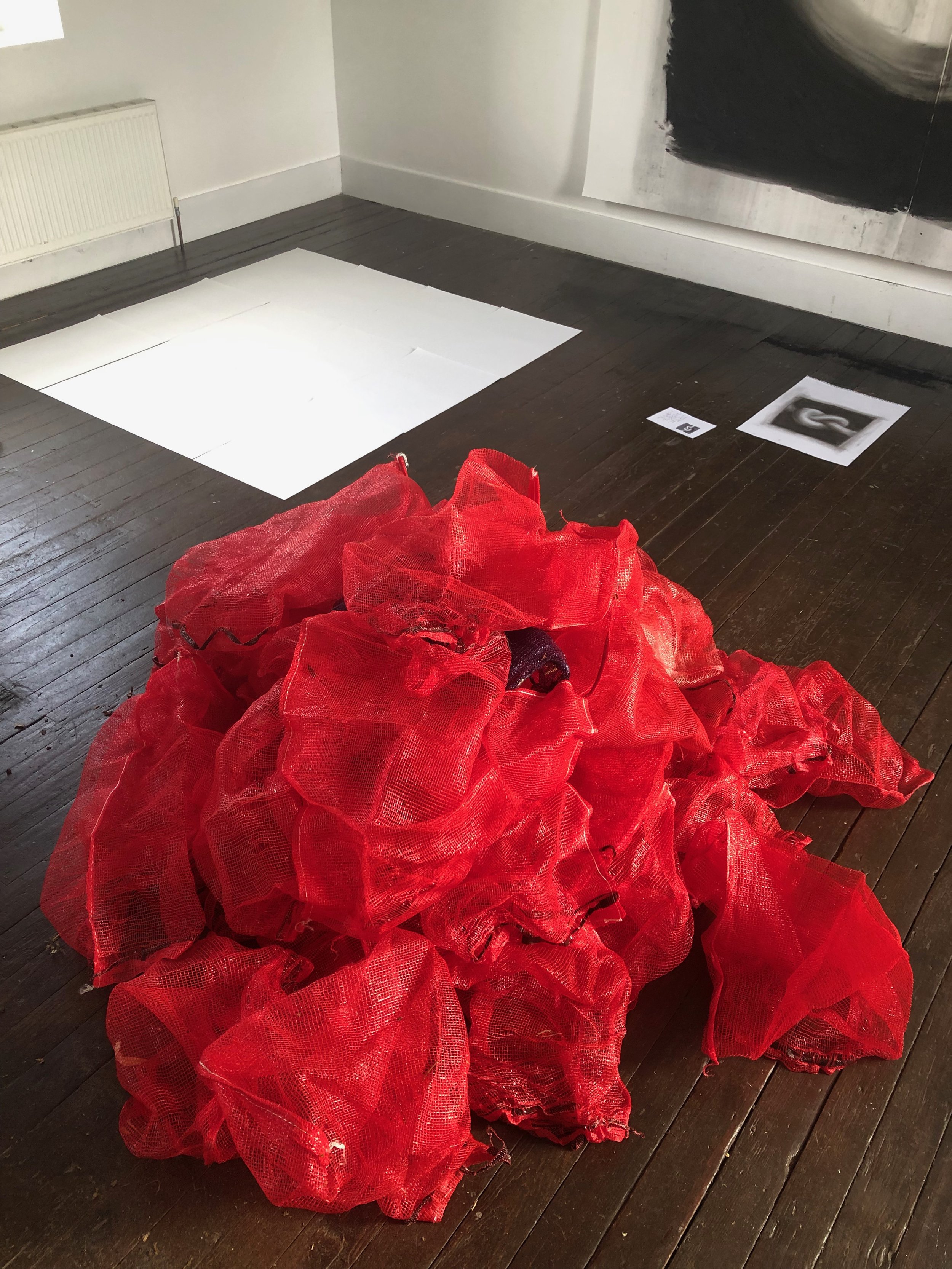

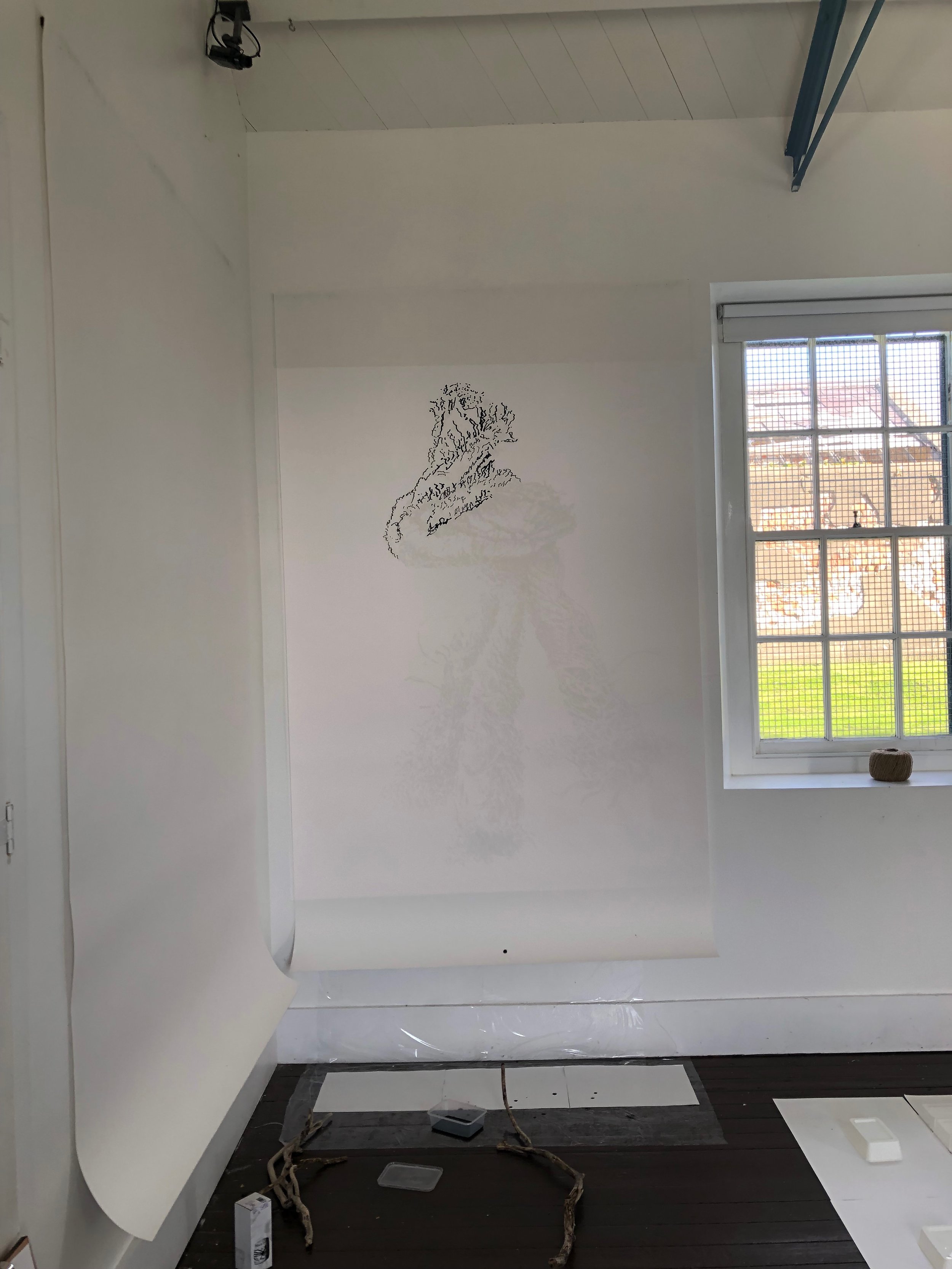

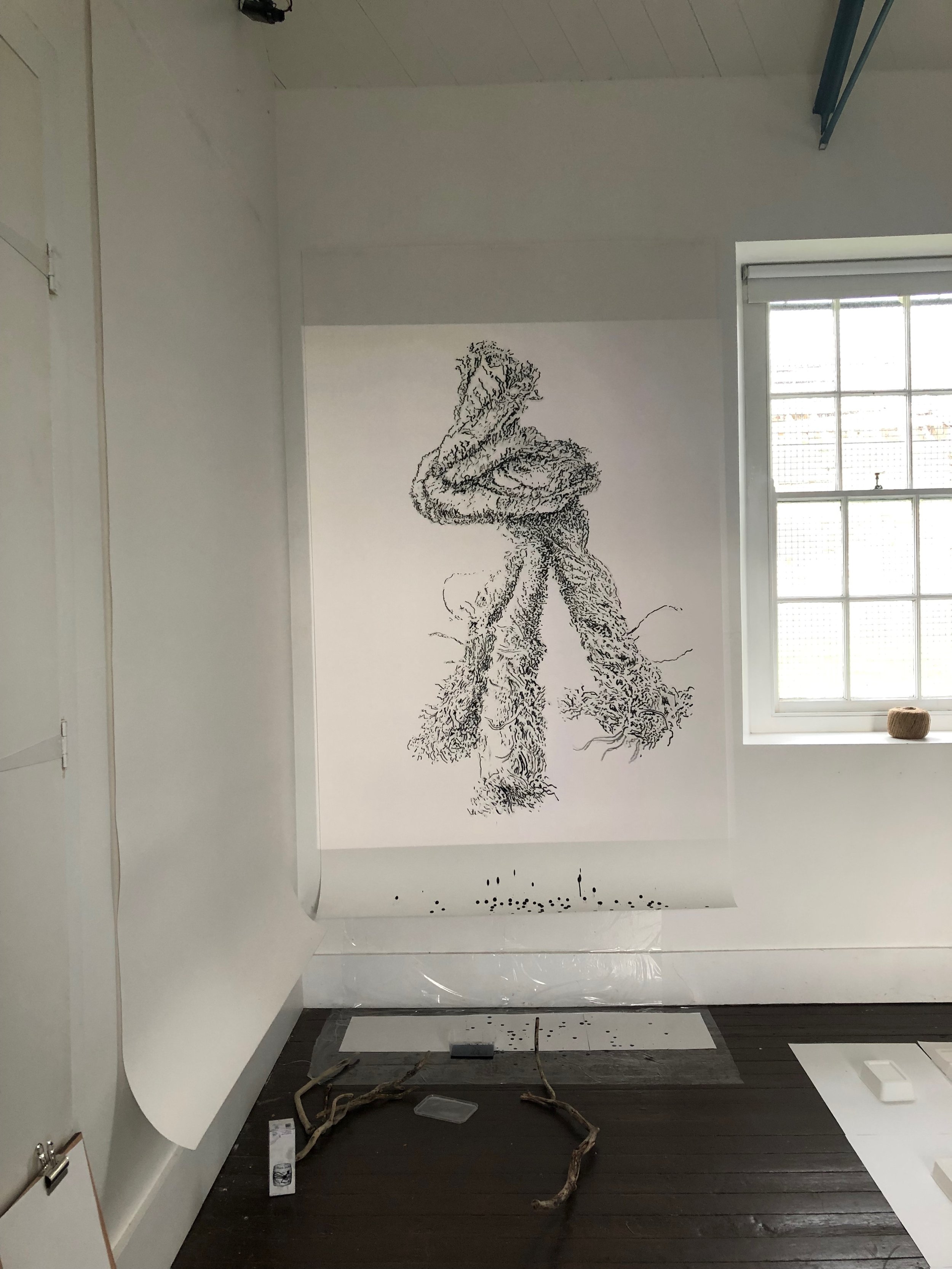

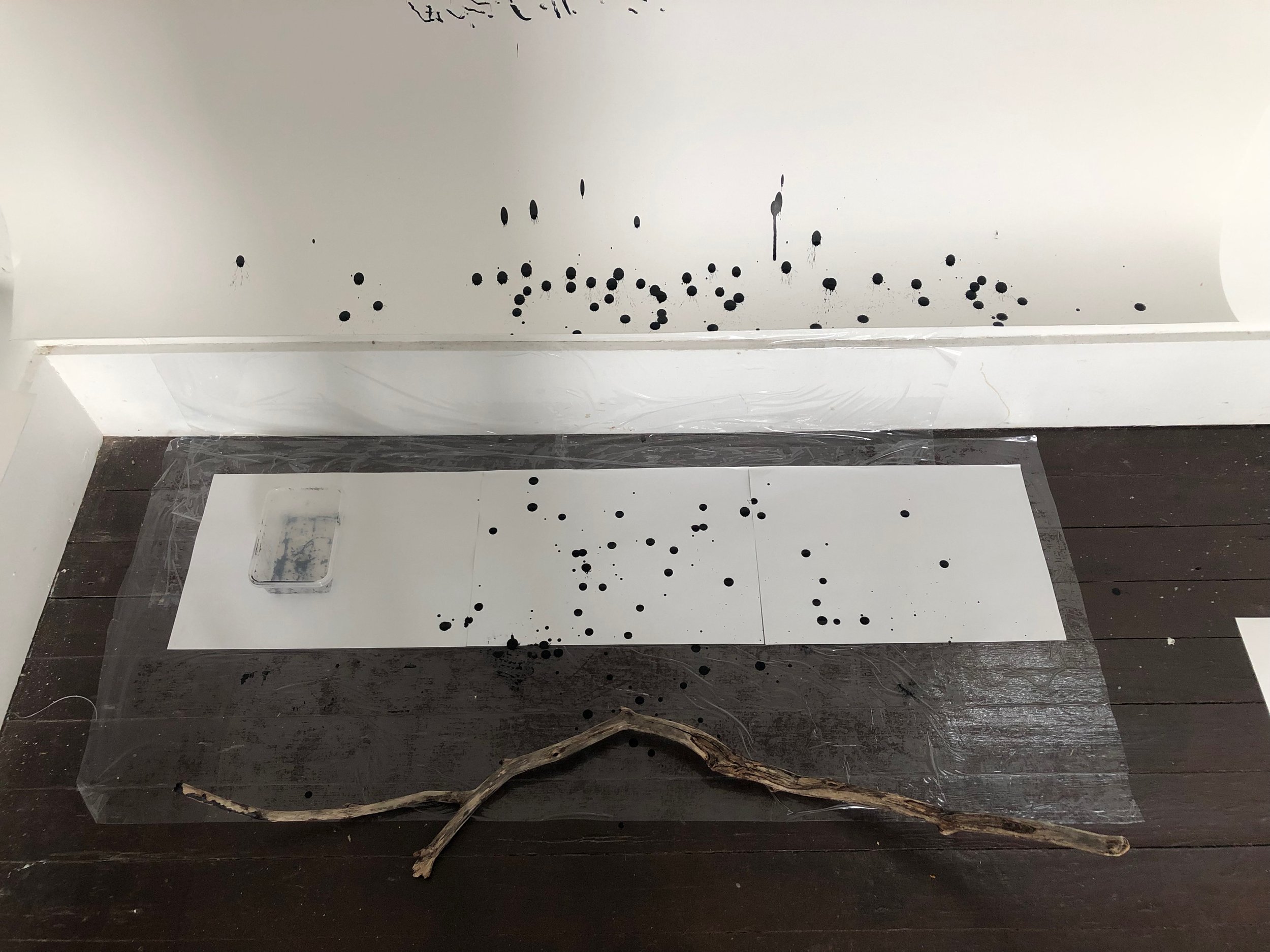

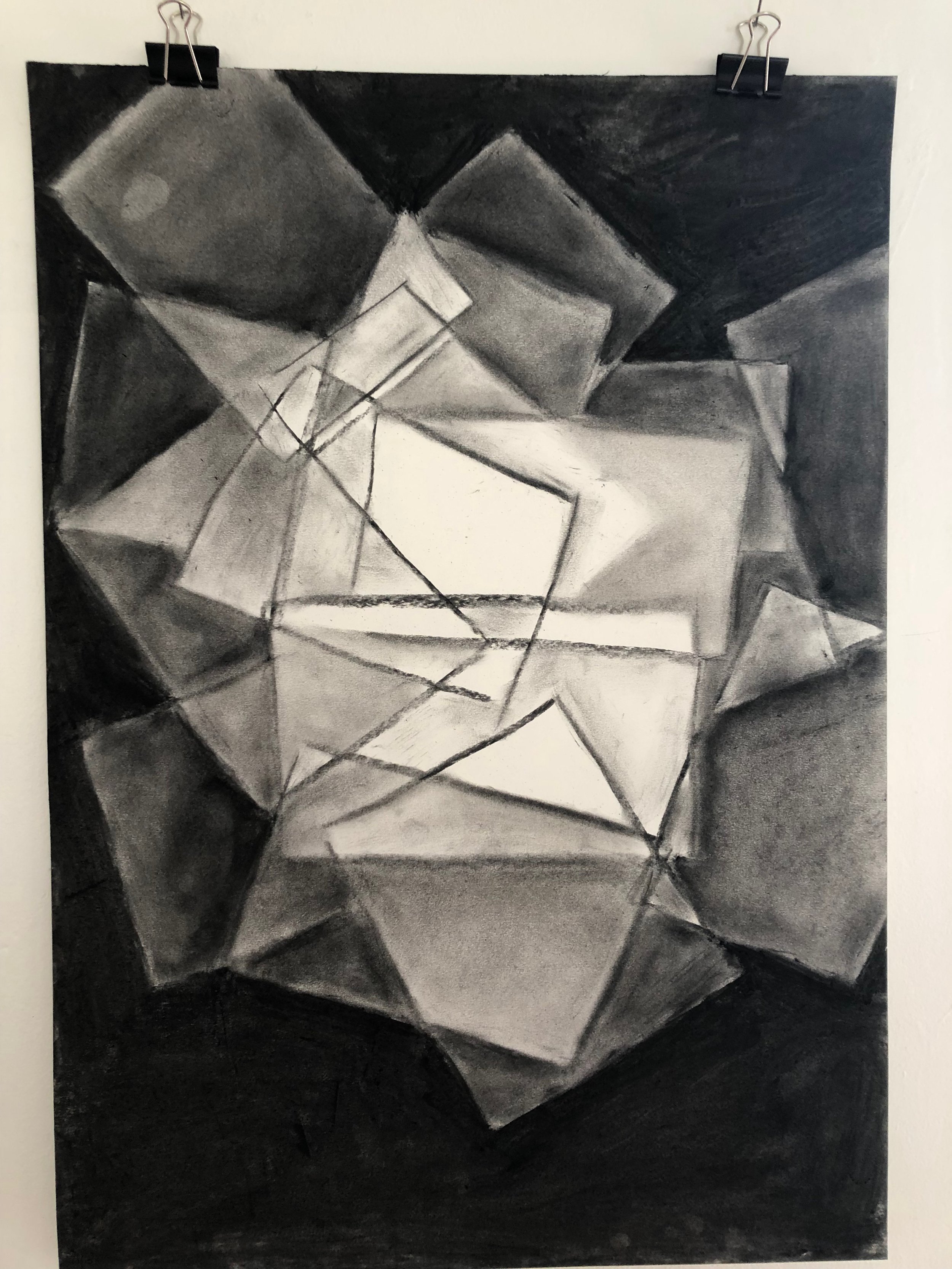

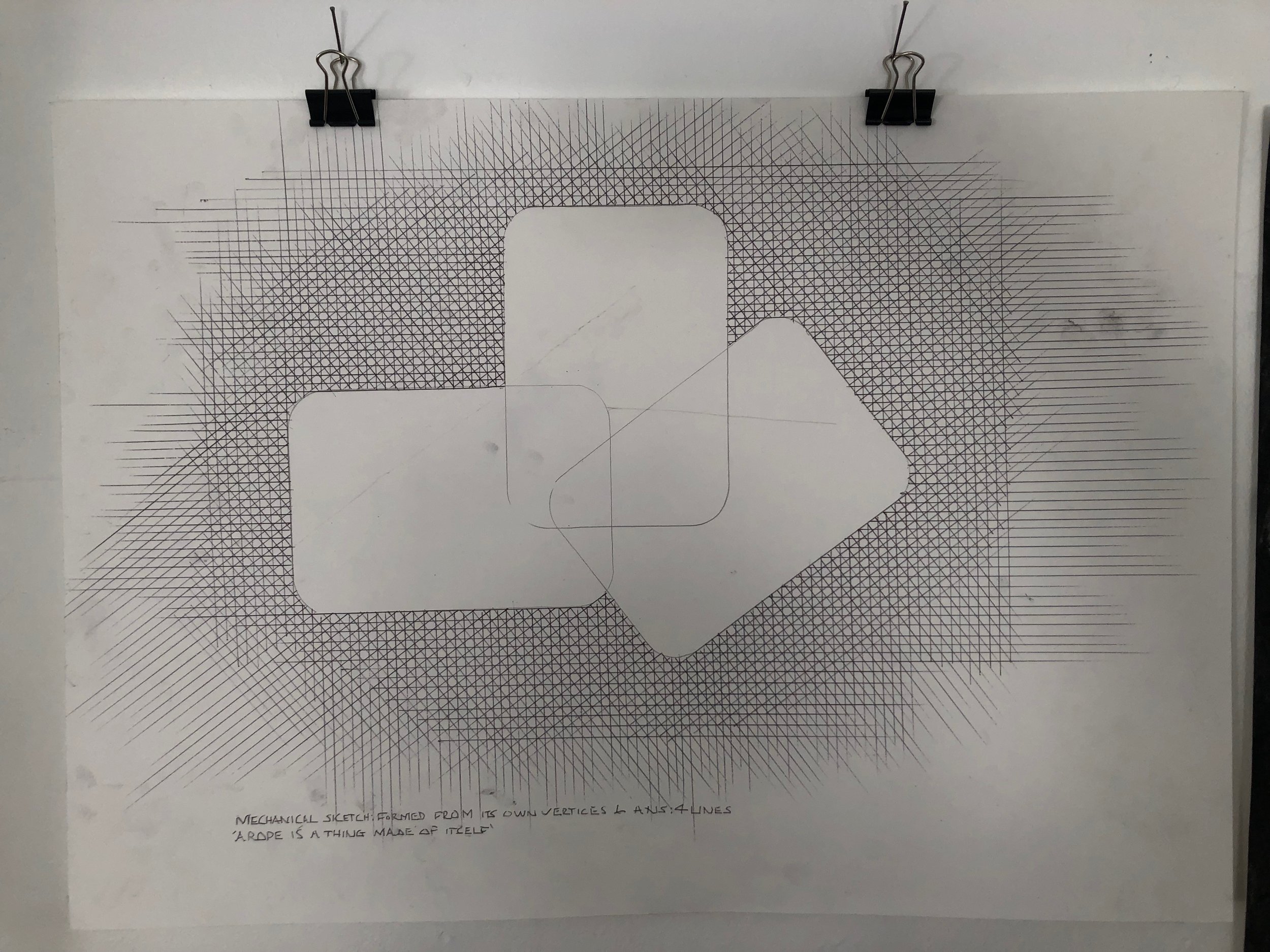

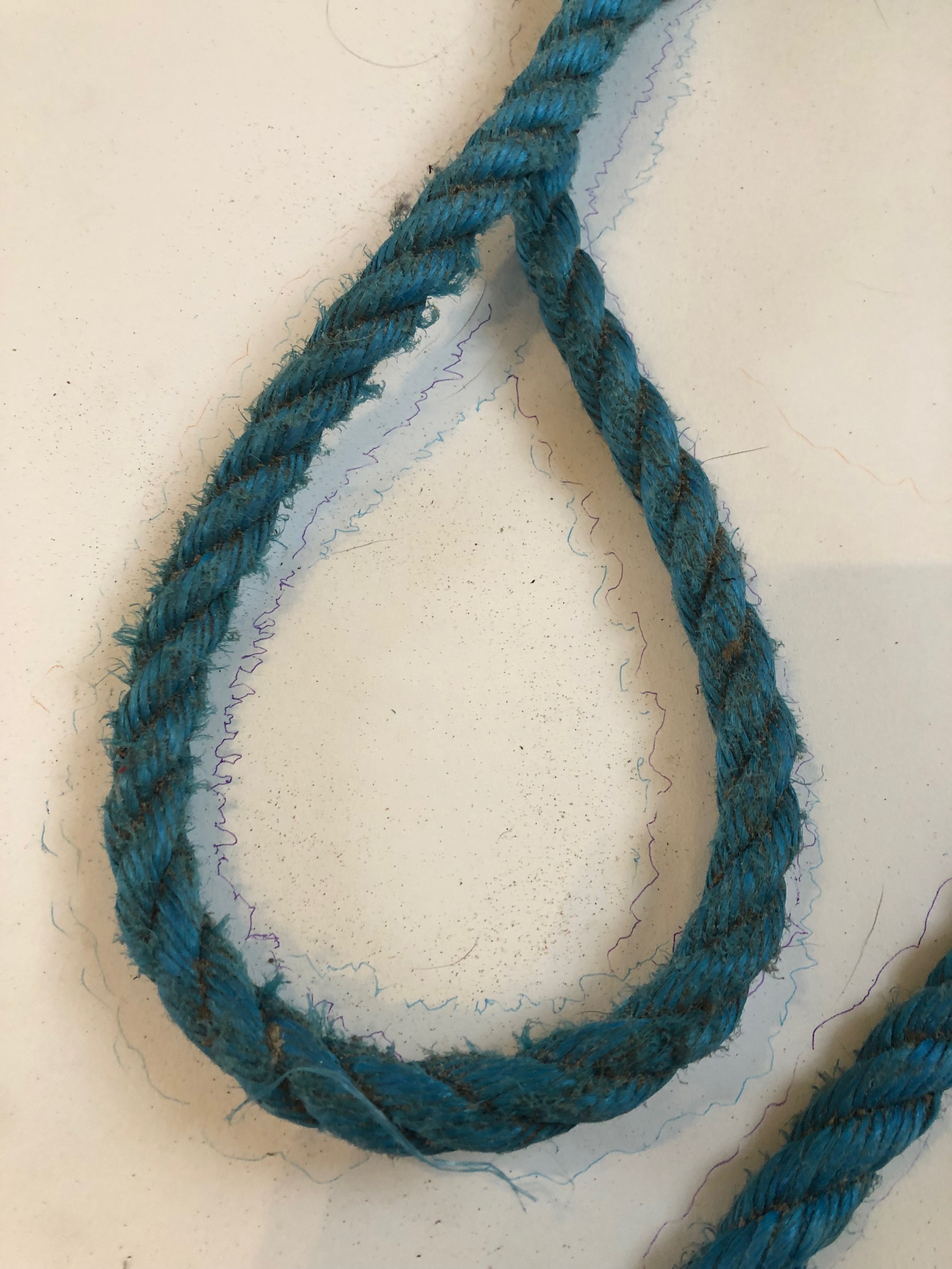

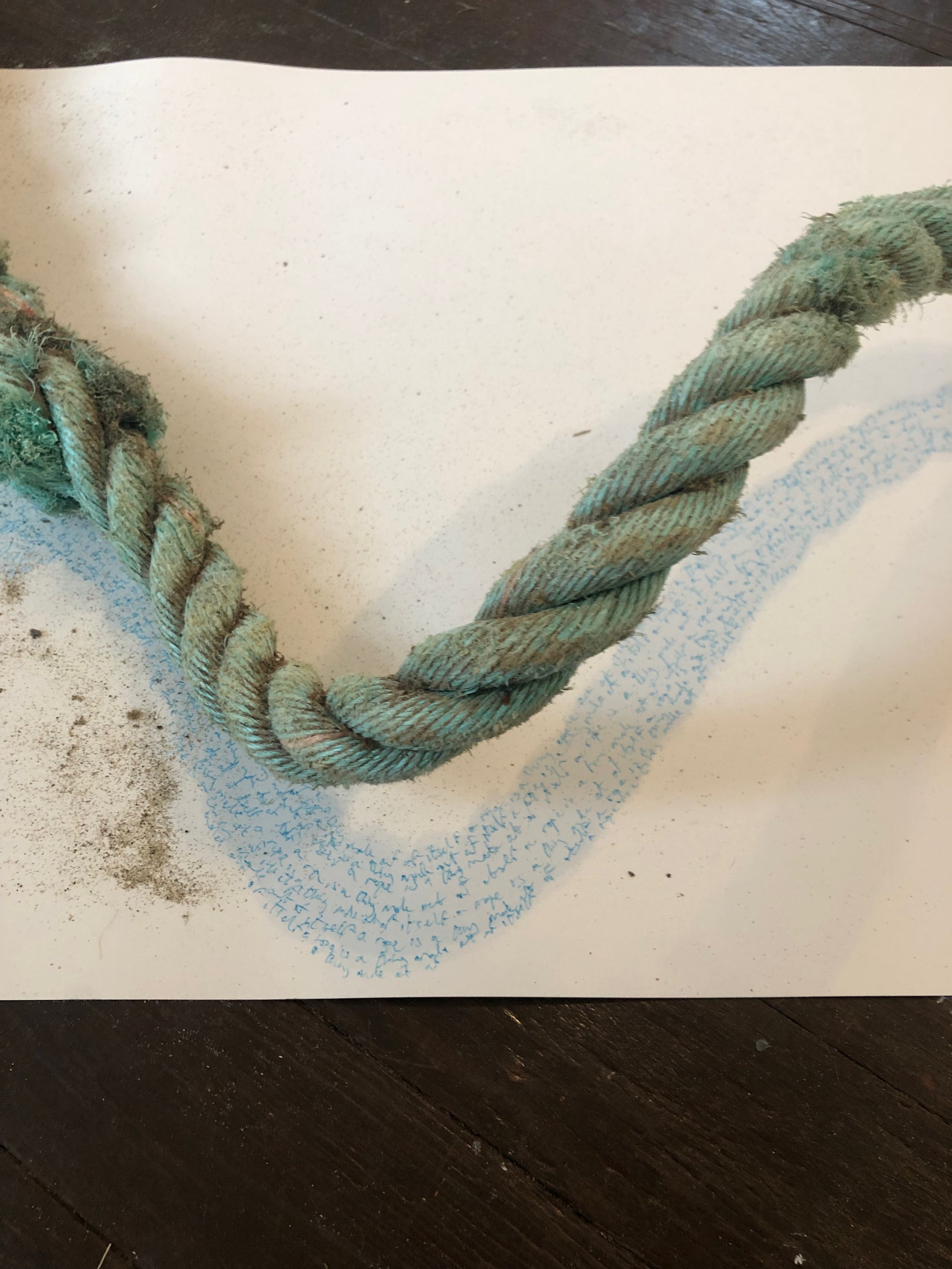

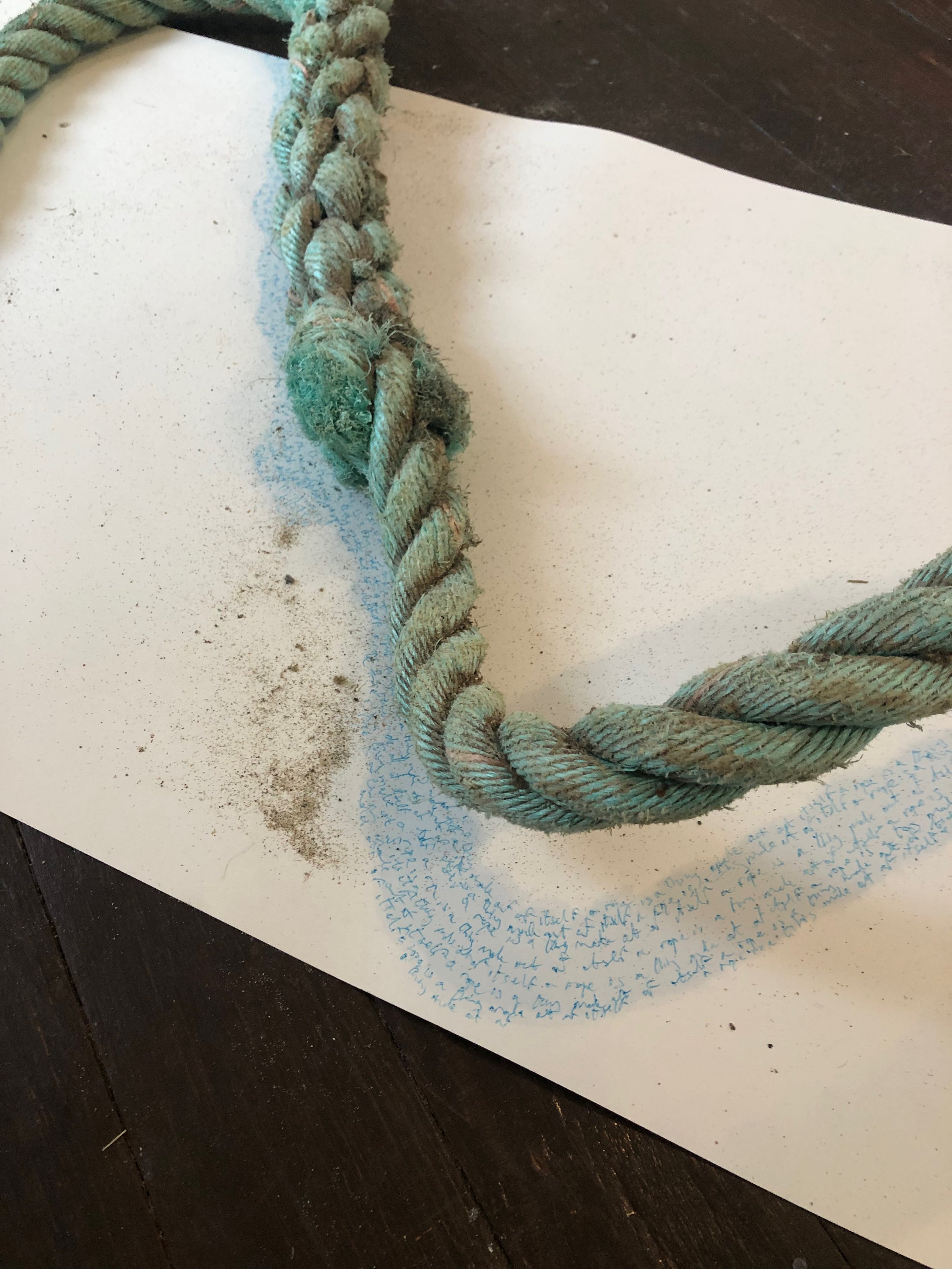

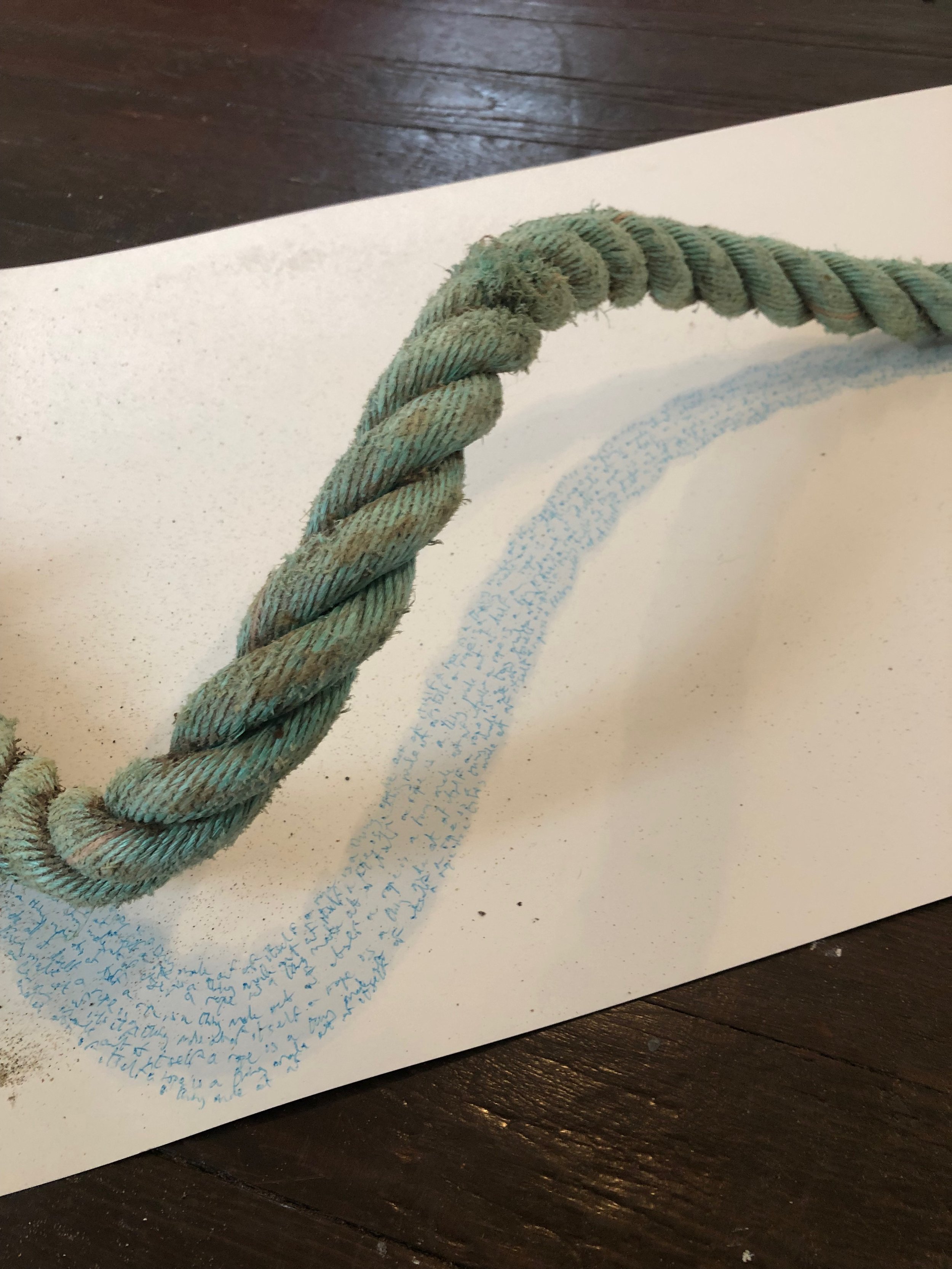

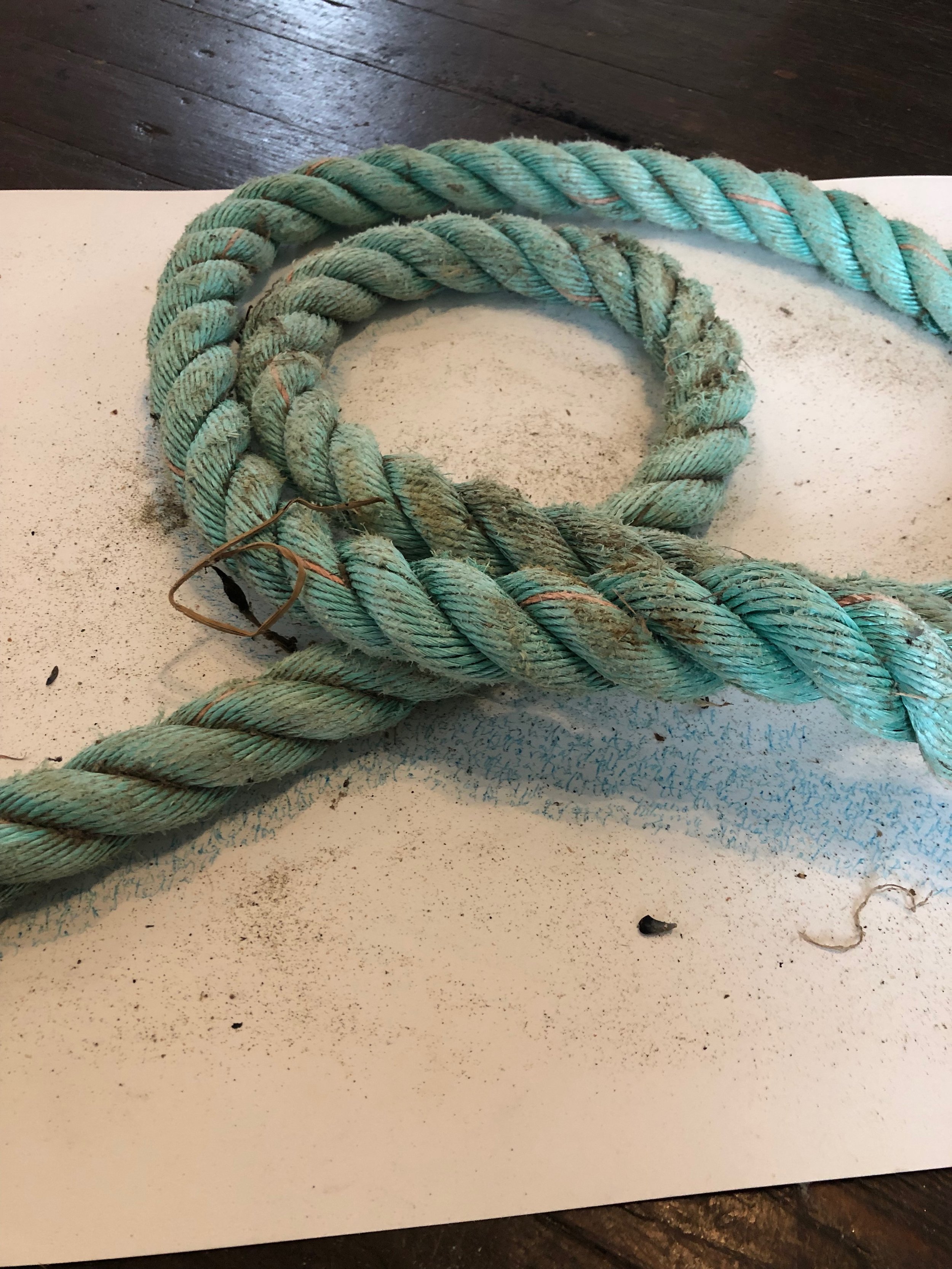

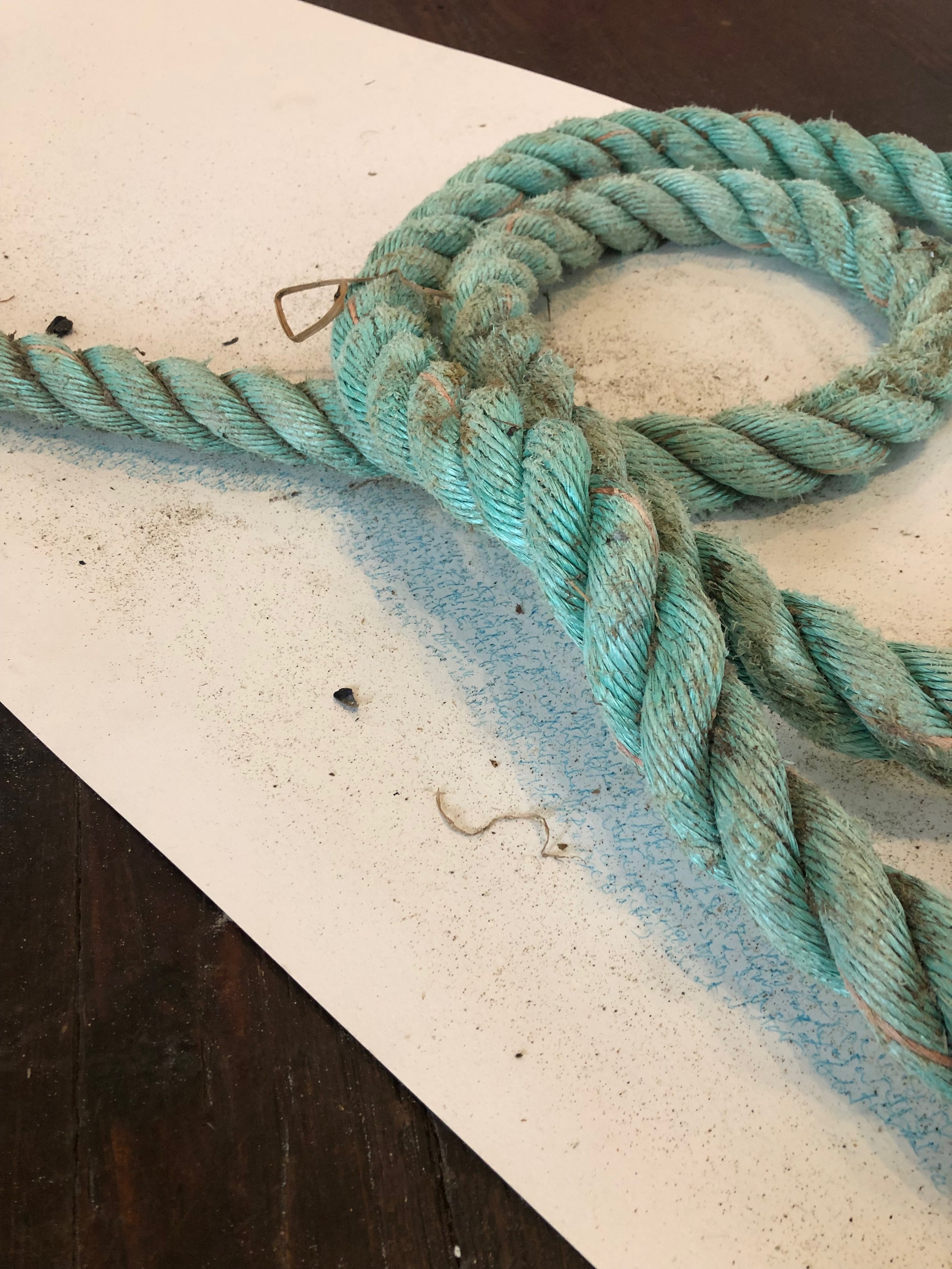

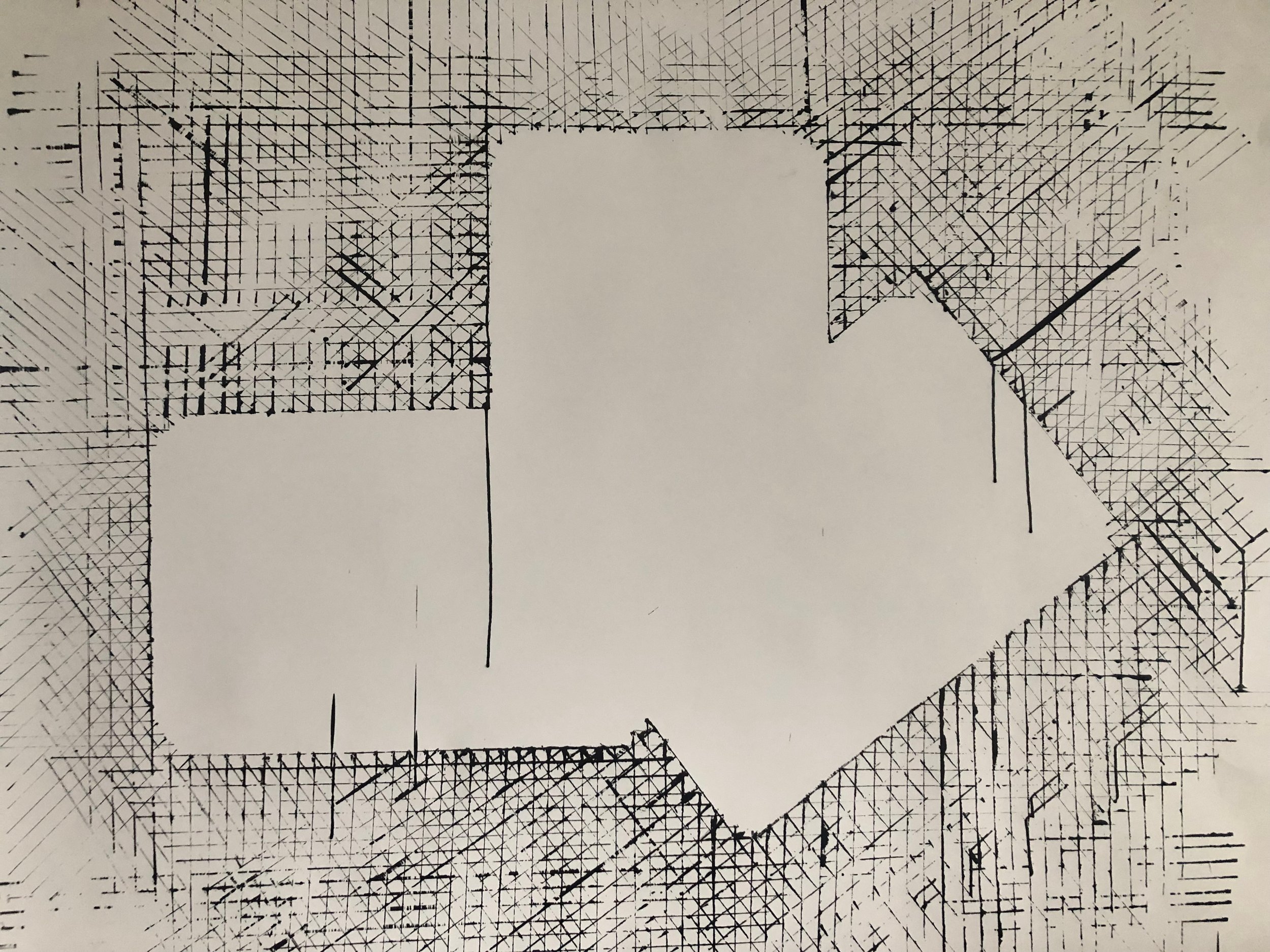

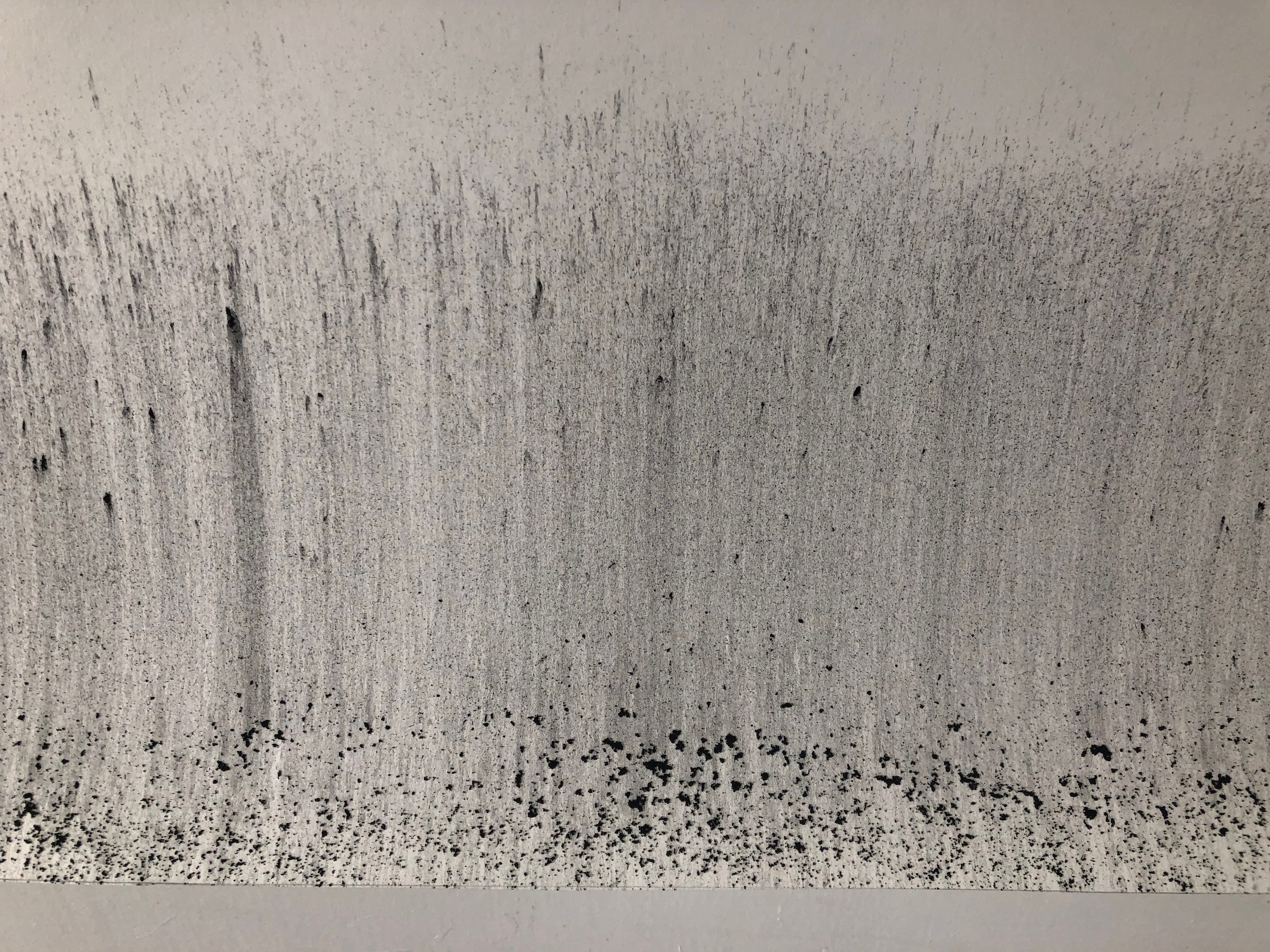

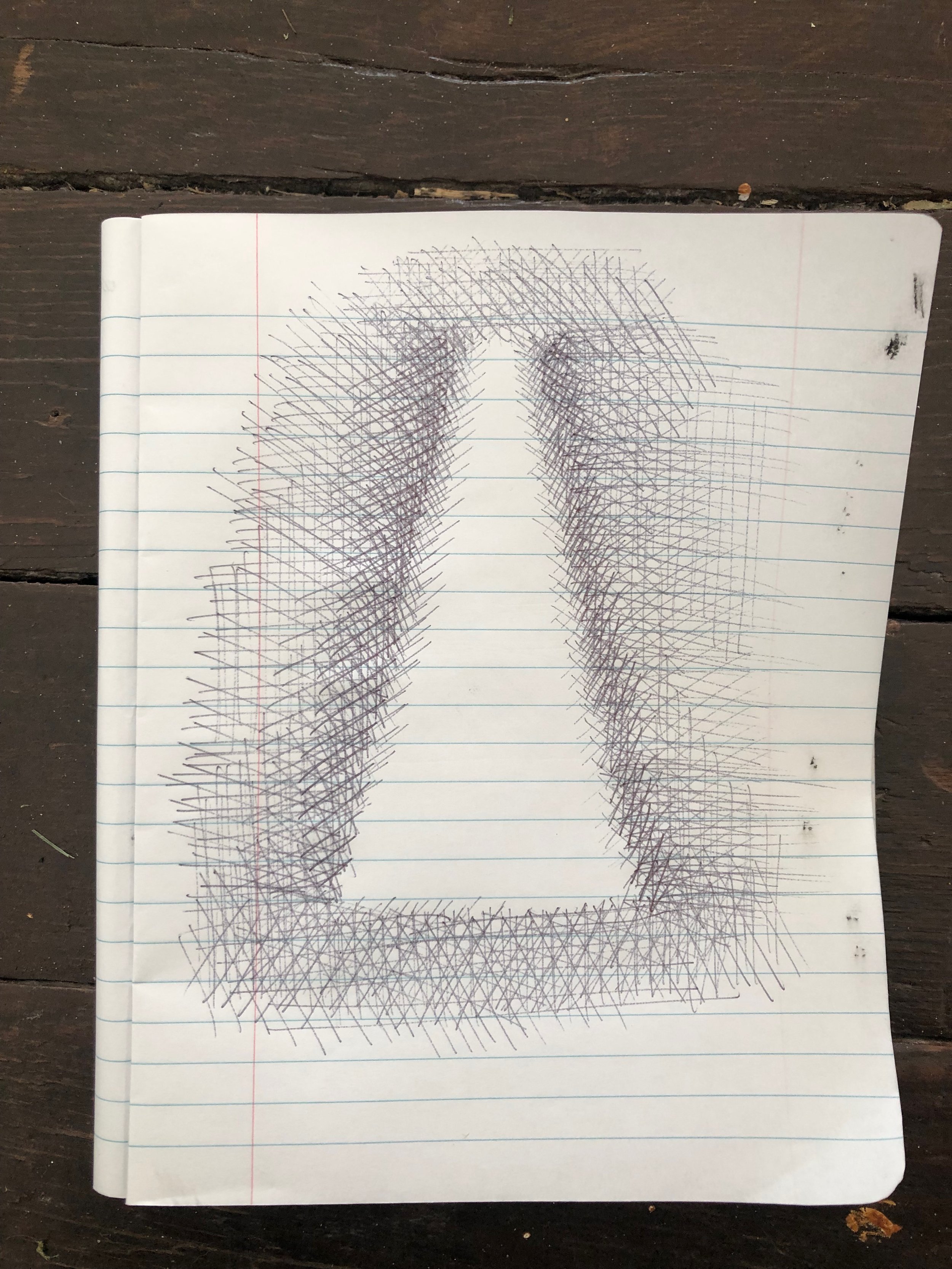

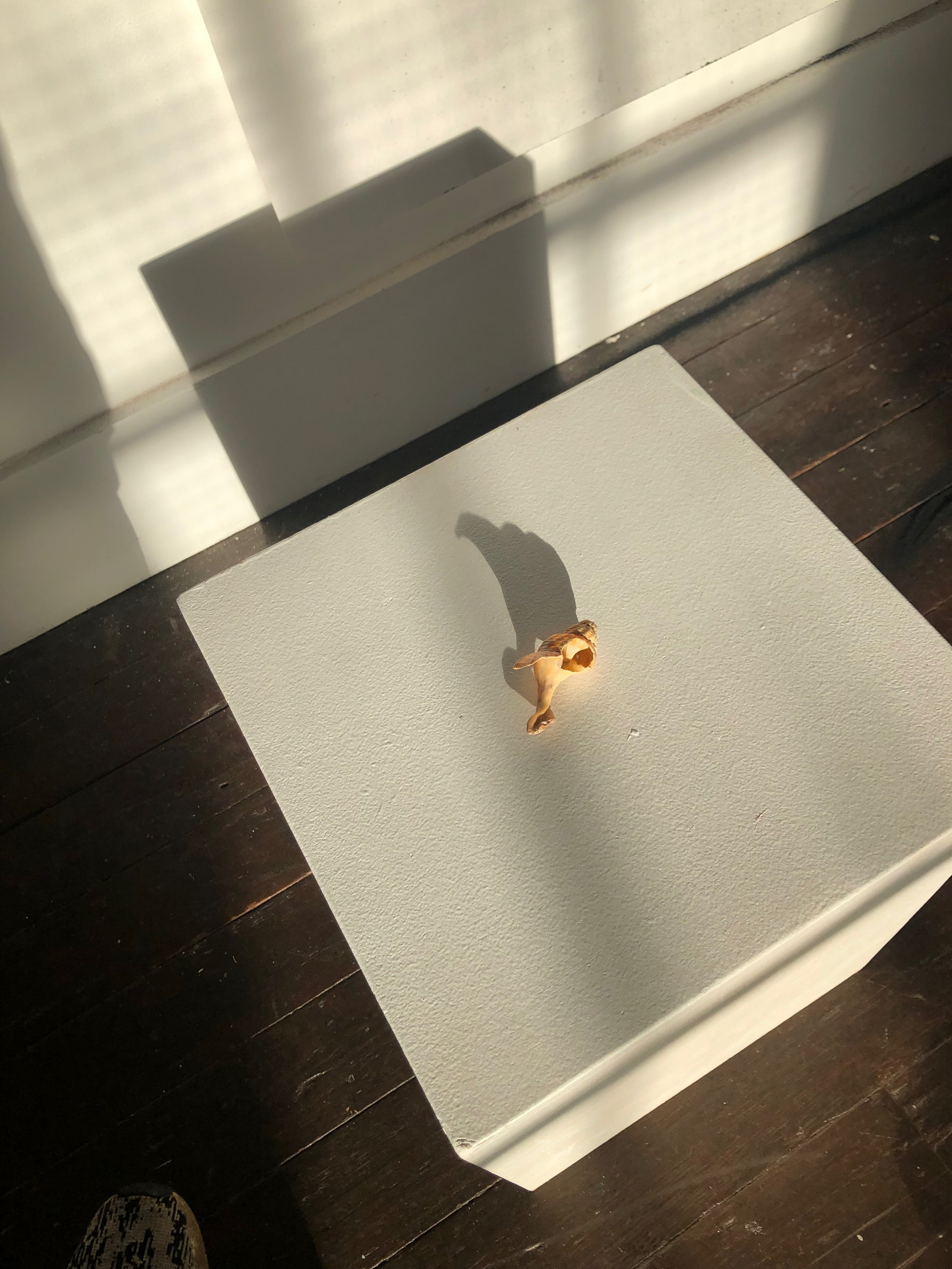

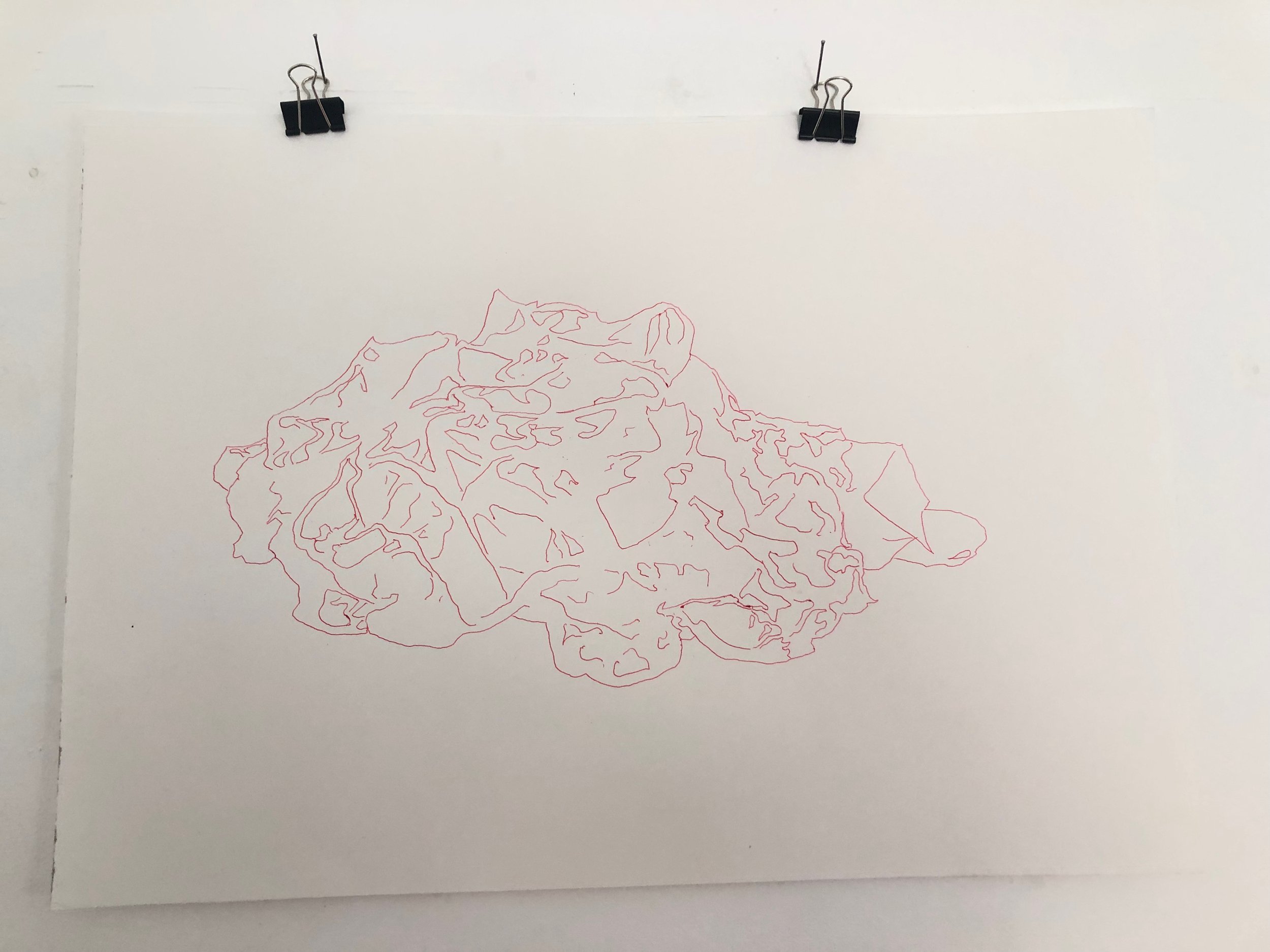

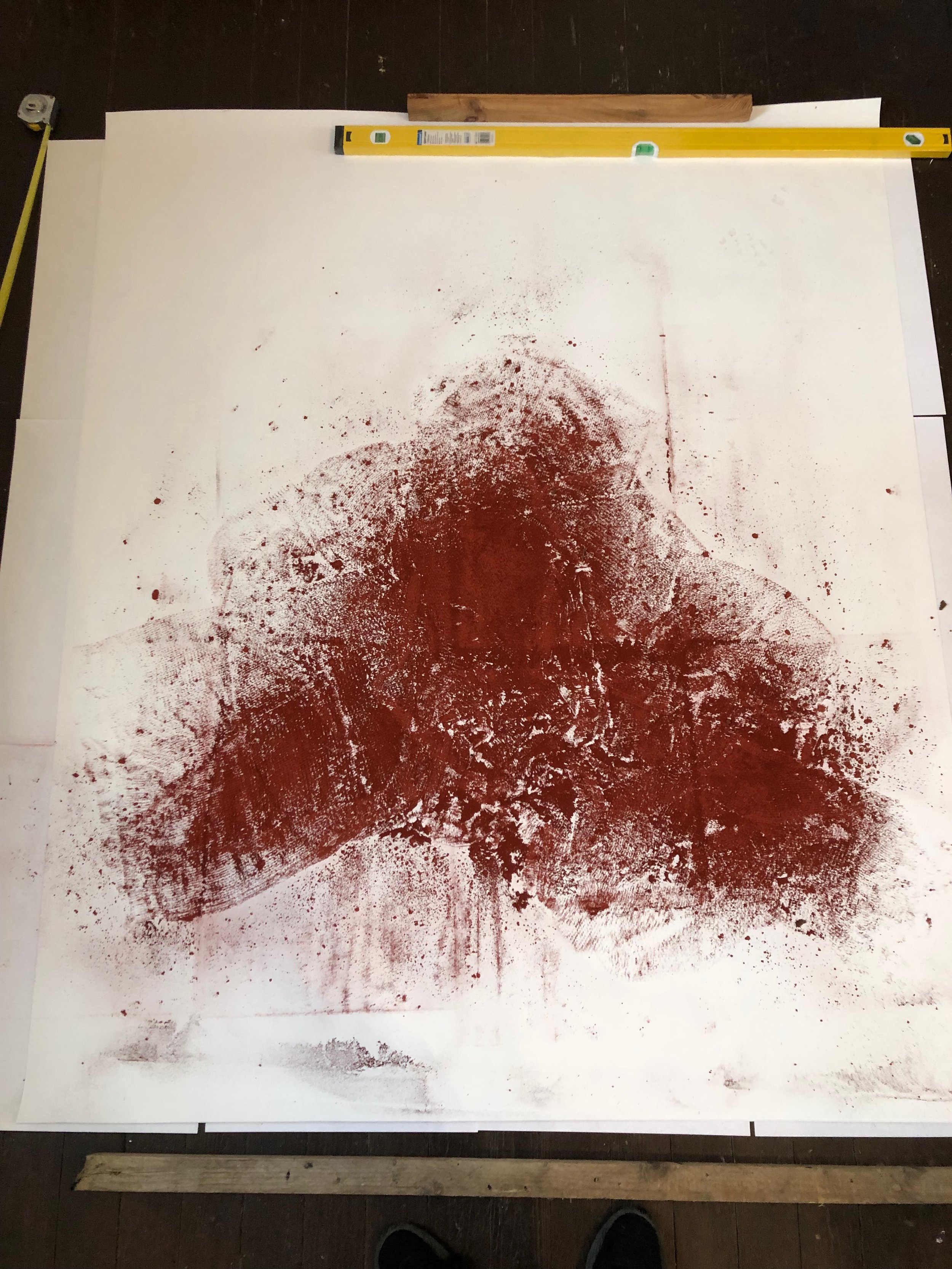

For this new exhibition at Artlink, McCardle brings a series of drawings of different sizes, ranging from small sketches in pen to large format drawing in charcoal where he seeks the emergence of abstract and unpredictable figures in this exercise of translating the image from one medium to another: the small format sketch to the large format drawing. These drawings will be accompanied by objects from everyday life, such as rope and plastic containers. Objects that, as McCardle explains, have an intrinsic utility, but nevertheless both represent the disposable.

For McCardle both objects (rope and plastic containers) utility is challenged by the temporary immobility between uses; ‘the ropes are found, the take-away containers no longer contain anything. Instead, they become users of the space itself, which is fast becoming a precious commodity within the economy of modern life’. In drawing these objects, Aodán McCardle intrinsically reconsiders their utility while at the same time respecting them as material beyond their initial intention.

Thus, McCardle uses these seemingly simple objects to complexify them through drawing, a drawing that he understands as an action in space and time, remaining in the room, creating a sense of a studio within the gallery.

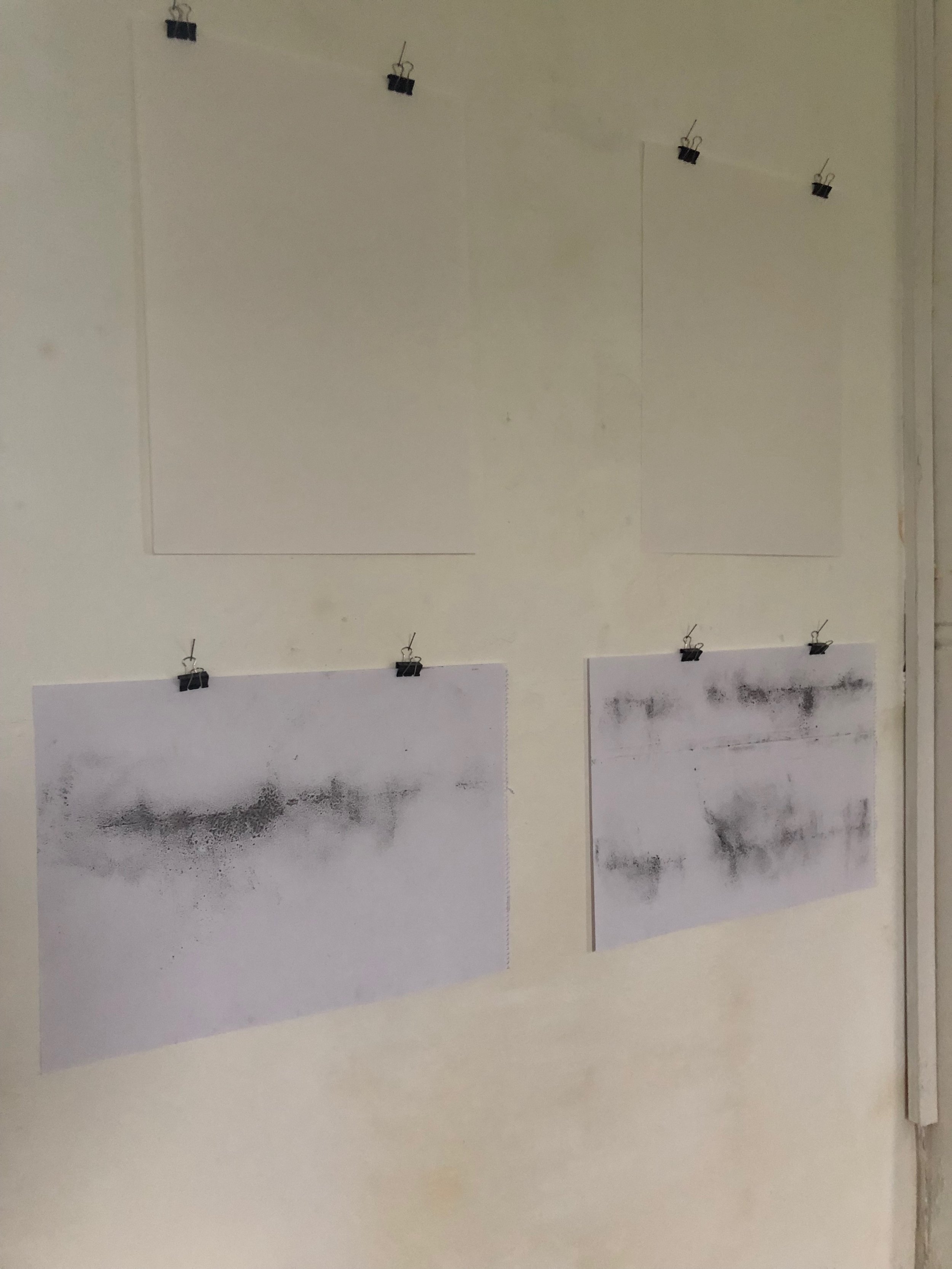

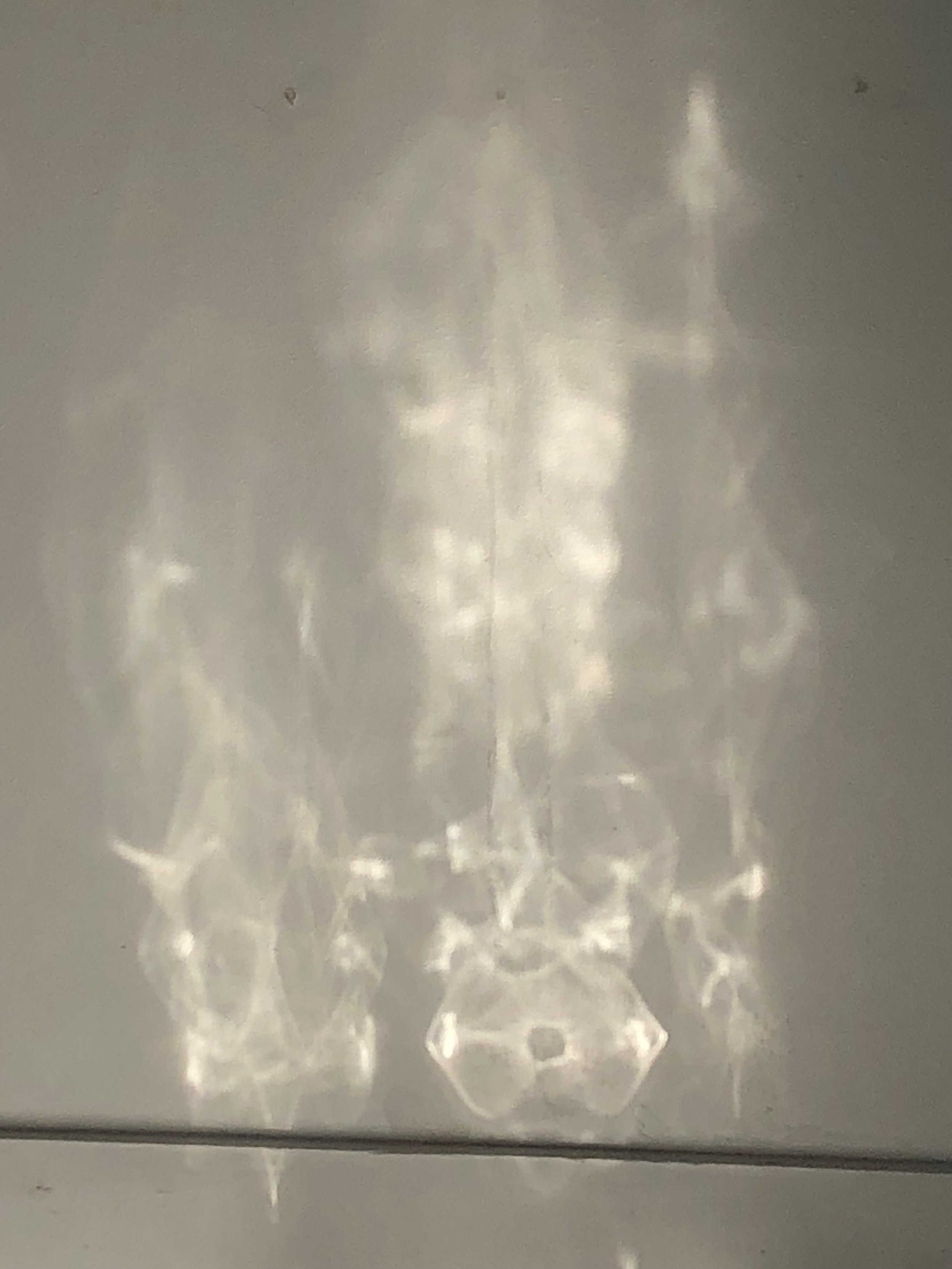

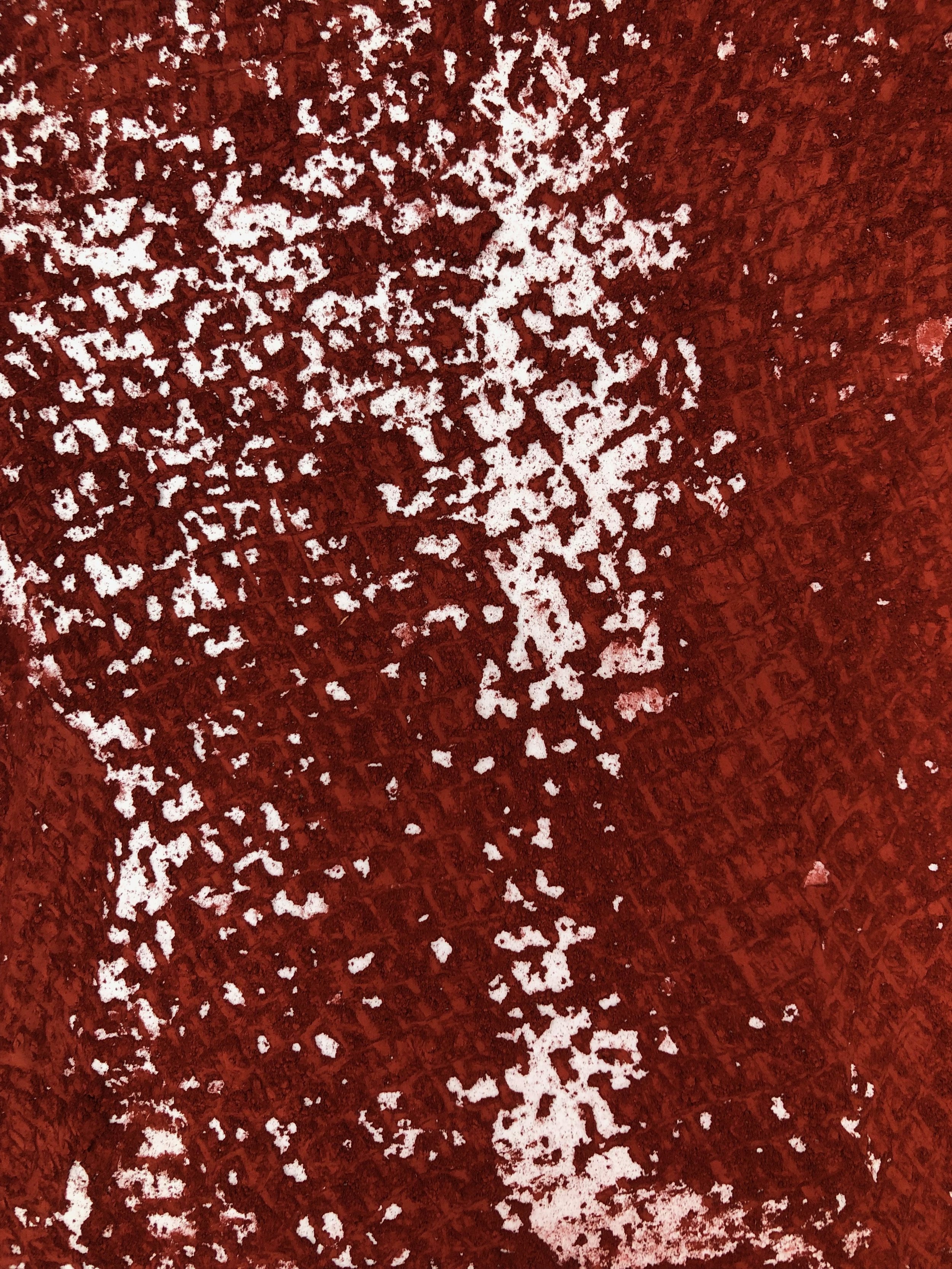

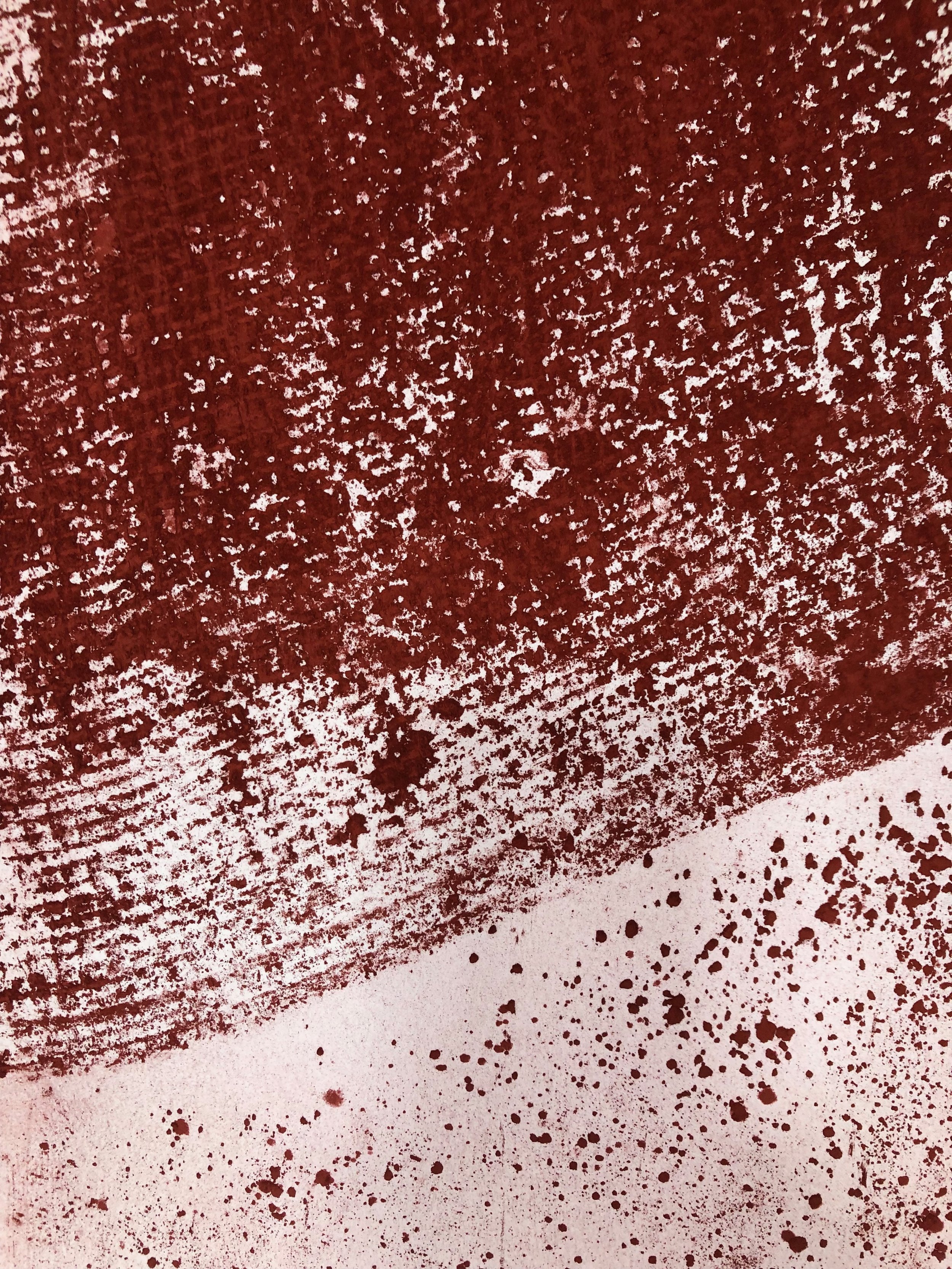

Aodán McCardle situates the act of drawing alongside writing as an act of discovery where drawing is as writing, and writing is as drawing. This arises in a performative context where the artist’s spontaneous performance uses charcoal and chalk to write or to draw body lines in real situations. In his performance, McCardle understands his body as a place, or as a topography from which to negotiate the theme of the environment and the context within a given performance. So, the trace left by the body as a drawing is an acknowledgment that someone was here, that something happened; it is a mark in space that incorporates an experience: a sign, a mark, a writing.

It would seem that these charcoal drawings in the gallery are like the charcoal and sienna clay drawings and cave carvings, as they are not intended for contemplation and display, but rather tentative and exhaustive visual investigation as is all drawing and writing of the world around us.

Artlink and Aodán McCardle want to invite you to stay tuned in case you want to participate in the creation of some drawings that will be made during the exhibition, which will be open to the public daily from 8th October until November 7, 2022.